Against Thanksgiving

Public holidays in the U.S. are an eclectic mix of birthday remembrances, pagan traditions, war memorials, re-purposed pagan traditions, and religious festivals, with the one constant being near-omnipresent commercialization. An exception is Thanksgiving, where the only expectation is that families and friends should come together over an (admittedly extravagant) dinner and count their collective blessings.

This dinner, and what’s required to put it on the table, is part of what makes Thanksgiving a particularly evil day.

Since becoming a vegan a few years back, I’ve been asked some variant of the question “so why don’t you eat meat?” about once per meal. Initially, my answers were probably clumsy, since my descent from (lactose-intolerant) omnivore to pescatarian to vegetarian to vegan felt more intuitive than intentional.

But over time, with many repetitions, I’ve honed in on what I think are the best arguments in favor of a plant-based lifestyle. And this year, since I’m skipping Thanksgiving dinner altogether, I’ll be serving this instead.

The arguments can be divided into three appetizers (environmental sustainability, food security, and individual health) and a main course (animal suffering). And for dessert, I’ll include a selection of the most common objections to veganism, including one I even find compelling.

- Appetizers

- Main course (animal welfare)

- Dessert (common objections)

- What about lions?

- What about people who need to eat meat?

- What about capitalism, man?

- What about the nutrition deficiencies in a vegan diet?

- What about bacon and cheese???

- What about all the water it takes to make almond milk?

- What about plants, don’t they feel pain too?

- What about cultural traditions involving animal products?

- What about people who rely on work in the animal agriculture industry?

- What about my cage-free, humanely raised, organic cricket flour?

- What about the farm animals that wouldn’t otherwise exist?

Appetizers

Although each of these three arguments might be an independently sufficient cause to go vegan, I consider them all pretty straightforward. Being mindful of the length of this post, and the risk of a Gish Gallop, I won’t spend much time here.

Environmental sustainability

Climate change literally keeps me up at night, and the recently released Fourth National Climate Assessment did nothing to help me rest easier. Here are a few choice quotes from the truly frightening report:

Climate change affects the natural, built, and social systems we rely on individually and through their connections to one another. These interconnected systems are increasingly vulnerable to cascading impacts that are often difficult to predict, threatening essential services within and beyond the Nation’s borders.

While mitigation and adaptation efforts have expanded substantially in the last four years, they do not yet approach the scale considered necessary to avoid substantial damages to the economy, environment, and human health over the coming decades.

If you’re not convinced that climate change is real, or that humans are culpable, I’d encourage you to read the associated Climate Science Special Report, and my other post on the topic.

Taking man-made global warming as a given, the environmental argument for veganism is simple: animal agriculture accounts for 18% of global CO2e emissions, and represents the lowest-hanging fruit for most meat-eating Americans, since the consumption of animal products is nearly always optional.

Food security

Climate change aside, humanity is barreling towards another, more fundamental crisis of global food security. Despite 9000 years of selective breeding, modern advances in farming techniques, and the advent of GM crops, we’re rapidly approaching the theoretical limit of humans that can be supported with anything resembling our current agricultural system.

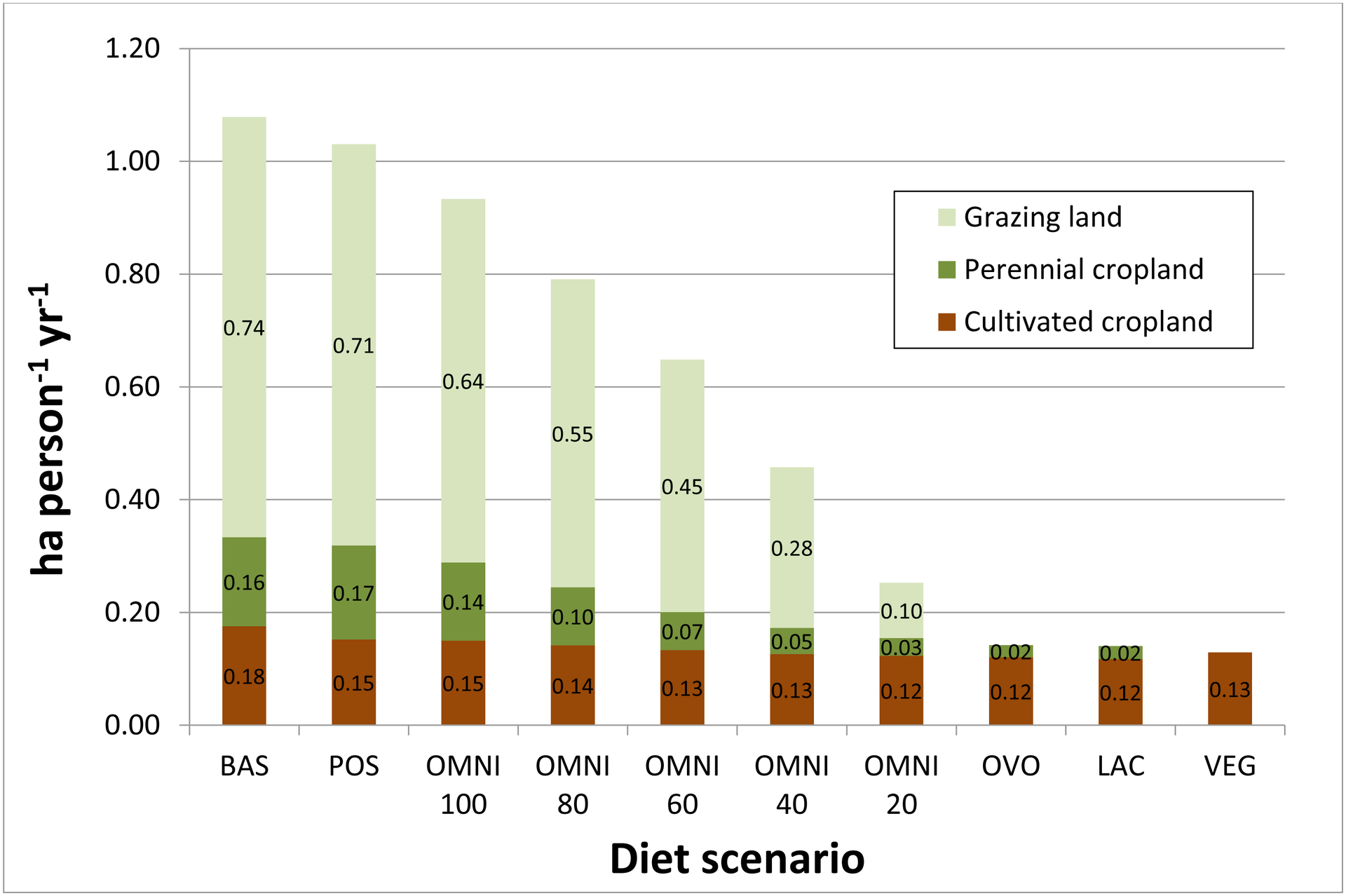

A recent study compared the land requirements of ten different diet scenarios, concluding that veganism required the lowest utilization of any diet:

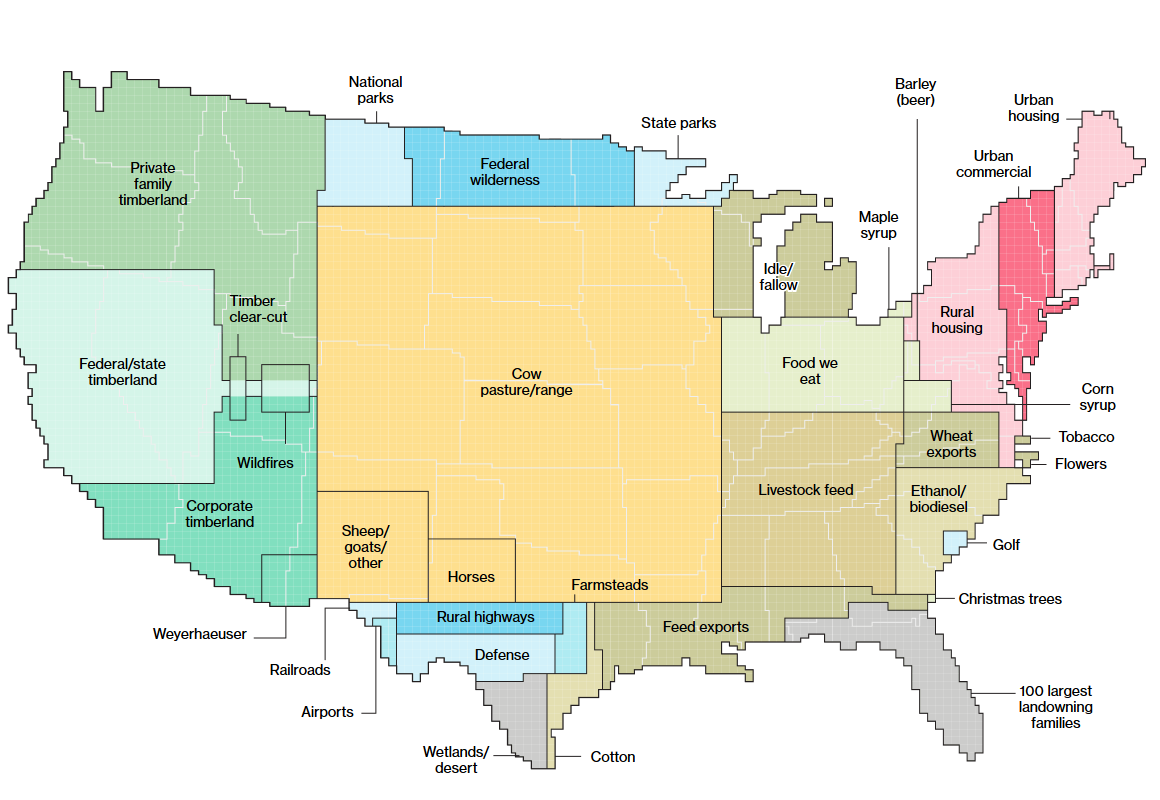

One caveat is that other vegetarian and reductionarian diets might utilize existing resources more efficiently, allowing for a slightly higher “carrying capacity” (sustainable population). Still, the relative land use of of the animal agriculture industry is staggering, as demonstrated by this recent Bloomberg visualization:

Without a global catastrophe, swift technological advancement, or some form of explicit population control, we seem collectively determined to fill the earth with as many humans as possible. Feeding a steady state population of 10 billion will require a significant reduction, if not total elimination, of meat from our diets, or we risk widespread food shortages and famine.

Individual health

Most vegan health claims focus on the individual, through the lens of typical dietary health benefits. A 2017 meta analysis of observational studies showed favorable results for plant-based diets across these metrics, concluding:

This comprehensive meta-analysis reports a significant protective effect of a vegetarian diet versus the incidence and/or mortality from ischemic heart disease (-25%) and incidence from total cancer (-8%). Vegan diet conferred a significant reduced risk (-15%) of incidence from total cancer.

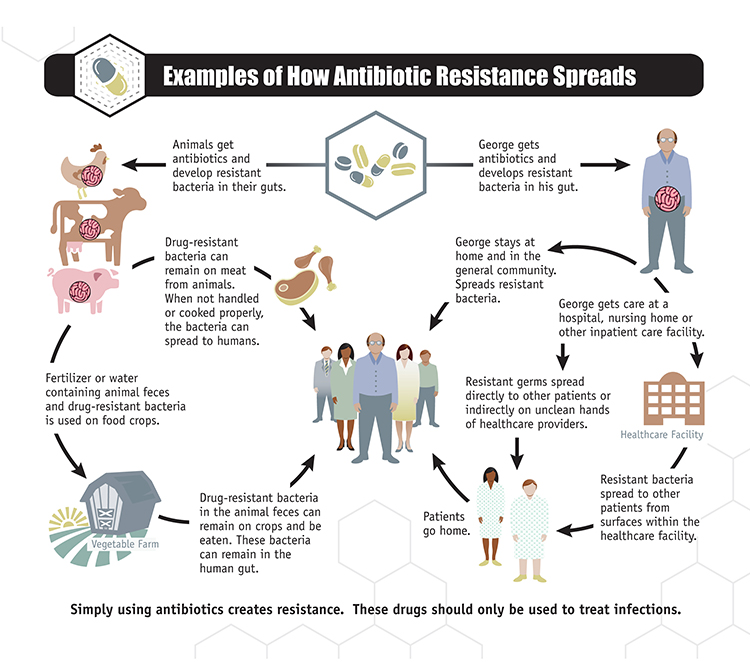

But the individual health benefits of veganism likely pale in comparison to the collective harm caused by animal agriculture. The most cited example of the pernicious effect of modern animal husbandry is the overuse of antibiotics in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), accounting for 80% of U.S. sales. The indiscriminate application of these drugs has helped foster new strains of resistant bacteria, which account for nearly one million deaths worldwide each year.

CAFOs also have harmful effects on their neighbors, as evidenced by the aftermath of Hurricane Florence this past fall. In addition to the millions of farm animals drowned, the floodwaters also breached the open-air lagoons of feces (below, in pink), contributing to the plight of nearby communities which already experience “higher all-cause and infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia, and higher hospital admissions/ED visits of LBW infants.”

In conversation about vegansm, I usually seek to downplay the supposed health benefits, being wary of promoting it as the next in a long line of dietary crazes. And as my college diet of orange Gatorade and hot dogs made clear to me, the human body can run on pretty much any fuel. But researching this section has made me more optimistic about the individual health benefits of veganism, and more concerned about the collective risks of our current appetites.

Main course (animal welfare)

Changing your mind is an uncomfortable business, if only because you remember so clearly what it’s like to be someone you now disagree with. I remember, for instance, being a person who liked to eat burgers, bacon, and eggs (sometimes all at once). I remember wearing wool sweaters, down jackets, and leather shoes (as recently as last year!). I vividly remember arguing with a friend that one person, any person, was worth saving over all other animals (provided, of course, that there were still enough animals left for people to eat).

I even remember writing a previous post, in which argued that animal lives should be discounted proportional to their relative encephalization quotient, long after I should have known better.

In short, I remember what it was like being a non-vegan, and how long it took me to fully come to terms with the importance of animal welfare. For me, the process ran in parallel through two distinct ideas:

- Most animals are capable of happiness and suffering

- The only things of moral importance are happiness and suffering

Finding evidence for 1 is complicated, because we can only ever be sure of our own individual subjective experience. It’s possible, for instance, that all animals (and other humans!) are just philosophical zombies, or that animal consciousness exists, but is so different that it is simply beyond comprehension, let alone comparison.

But common-sense arguments in favor of 1 are easy to find. For instance, on a geological timescale, we share a recent common ancestor, and many of the same neurological structures (including those associated with pain in humans) with most of the animals that we eat. Moreover, even distantly related animals respond to painful stimuli in exactly the way we would expect if they were experiencing pain. As David Foster Wallace noted in his essay Consider the Lobster:

If you’re tilting it from a container into the steaming kettle, the lobster will sometimes try to cling to the container’s sides or even to hook its claws over the kettle’s rim like a person trying to keep from going over the edge of a roof. And worse is when the lobster’s fully immersed. Even if you cover the kettle and turn away, you can usually hear the cover rattling and clanking as the lobster tries to push it off. Or the creature’s claws scraping the sides of the kettle as it thrashes around. The lobster, in other words, behaves very much as you or I would behave if we were plunged into boiling water (with the obvious exception of screaming). A blunter way to say this is that the lobster acts as if it’s in terrible pain…

Arguing that animals don’t have a subjective experience requires an explanation for why they act as if they do, and is probably not the most parsimonious interpretation of the evidence.

For evidence in favor of animal happiness, just browse r/happycowgifs or r/animalsbeingbros, because a .gif is worth 1000 words.

A proper defense of 2 (and utilitarianism, generally) will require a post of its own, but for the sake of this argument, it’s only necessary to accept that happiness and suffering have moral importance, regardless of the medium in which they are experienced. For more on utilitarian philosophy see here, or watch the surprisingly excellent The Good Place.

Even if you aren’t entirely convinced of the merits of 1 and 2, you’re not in the clear just yet. The scale of potential animal suffering is so enormous that Pascal’s Wager applies, and even a small probability that farmed animals suffer should overwhelm other considerations. For instance, consider the plight of egg-laying chickens:

- Since only female hens lay eggs, male chicks are killed shortly after hatching by “suffocation, gassing, maceration, or electrocution.” Over 250 million die this way each year in the U.S. alone.

- The survivors often spend their entire lives in battery cages, stacked boxes built of metal grating, no bigger than a large shoe box.

- Through a process of artificial selection, modern egg hens lay 250-300 eggs per year, up from the 10-15 of their natural ancestors.

- It’s common practice for their beaks to be sheared off with a hot metal wire, and no anesthetic, to prevent stress-related pecking injuries.

- Hens are typically slaughtered before their second birthday, far short of their natural lifespan of 8 years.

Similar abuses are carried out on the whole spectrum of farmed animals, including turkeys, nearly 50 million of whom were bred and killed for dinner today.

A troubling thing about the animal welfare argument is that I suspect most people already agree, and yet still eat meat anyway. A recent poll showed that nearly four in five Americans want food industry to reduce farm animal suffering, and another report suggests that around a third believe that animals deserve the same rights as people, but only 3% eat a vegan diet. To me, those numbers imply that there are at least 100 million Americans living in a state of severe cognitive dissonance.

And among those 100 million are people I know and care for, including some who might be reading this. Imagine, for a moment, what it’s like to be a vegan in America today. Nearly all of your friends and family, the public figures you admire, and everyone you pass on the street is currently complicit in what you see as an ongoing moral atrocity. On some level, most of them know it’s wrong, and yet they all sat around that dinner table today, giving hopelessly insufficient thanks.

Dessert (common objections)

Some of the more frequently cited criticisms of vegans amount to implicit whataboutism, a form of the red herring fallacy. Instead of elevating the virtue of their position, practitioners will instead express a belief in universal vice and moral relativism, attempting to undermine the premise of the debate without directly engaging in it.

I remember doing this myself, when first confronted with the arguments above, and I’ve seen it from the other side as well, in conversations since going vegan. In order to address the understandable sentiment behind these objections, I’ve done my best to enumerate, categorize, and give a detailed response to each.

What about lions?

This is the most common “first” objection I hear, and it’s also one of the easiest to dispense with. Lions are obligate carnivores, and require nutrients found only in meat to survive. While I support the ongoing research efforts into reducing wild animal suffering caused by predation, I’m not aware of any practicable solutions at the moment.

Thankfully (and even though we have canine teeth) humans are omnivores, and do not require animal products to survive and thrive.

What about people who need to eat meat?

This is the general case of the following cliché:

What about if you were stuck on a desert island, with only a pig and no other food. Would you eat it in order to survive?

Desert island criticisms are so common that they have inspired a whole sub-genre of vegan memes. Here’s an example that speaks for itself:

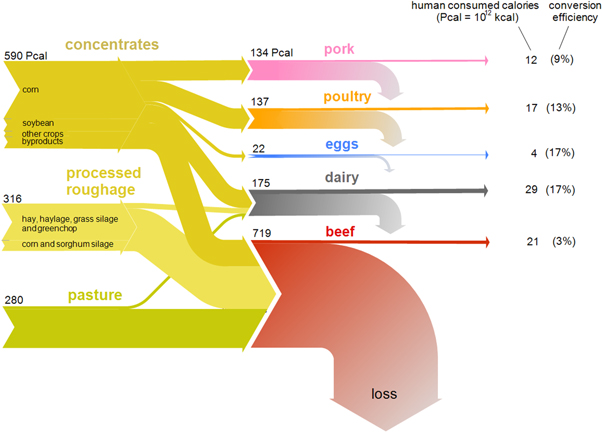

There’s a similar strain of criticism that paints vegans as Whole Foods elites, forcing their expensive luxury-vegetable lifestyle on the huddled masses who just want to eat their Whopper in peace. The truth is that healthy, plant-based diets need not be expensive, and should in fact be cheaper, since every calorie of meat requires 5 to 30 calories of feed to produce:

Given the moral importance of animals, I still believe that their wellbeing takes precedence over the optional dietary preferences of humans. But for the small percentage of people who have no choice but to eat meat for reasons of availability, our societal goal should be to provide better options, not excuse inhumane farming practices.

What about capitalism, man?

Another common criticism, especially from the left, is that focusing on individual consumption of animal products ignores the systematically immoral, profit-seeking corporate behavior that has, behind closed doors, turned what was once a symbiotic relationship between man and animal into a mechanized hellscape, oiled with blood.

I have no objection to this except to say that, while there may be no ethical consumption under capitalism, not all consumption is equally unethical. While not perfectly elastic, reduced demand for meat does reduce the supply, and therefore suffering, of farmed animals, and any good moral framework should account for this gradient.

What about the nutrition deficiencies in a vegan diet?

Much is made of the supposed vitamin B12, iron, and protein deficiencies of vegan diets, but this is hard to square with the findings of organizations such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, “the world’s largest organization of food and nutrition professionals,” which holds the position that:

appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits for the prevention and treatment of certain diseases.

This sentiment is echoed by leading health services in America, Canada and the United Kingdom. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest the average American consumes too much protein as it is.

There is also the case of vegan athletes, including Venus and Serena Williams, Kyrie Irving and a host of other NBAers, and fully 25% of the Tennessee Titans, who all thrive at the peak levels of their respective professions.

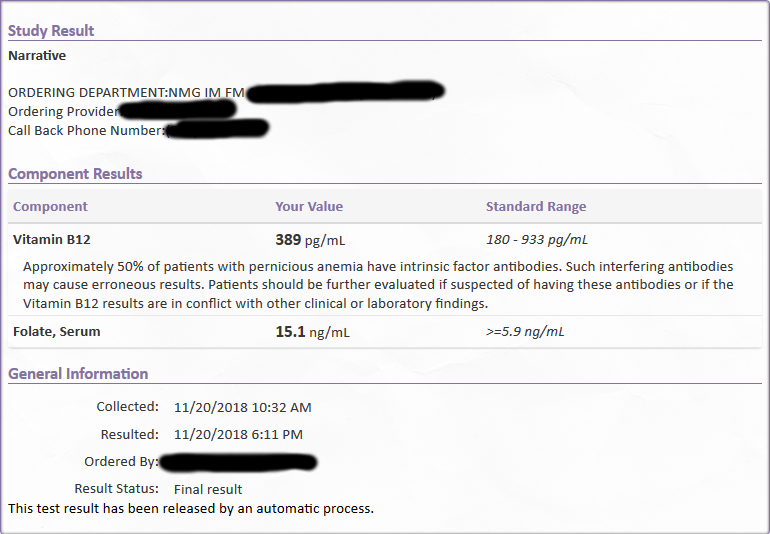

Finally, in the spirit of full disclosure, see below for my own test results, showing that even a vegan diet as careless as mine can be “healthy,” at least as far as B12 levels are concerned:

What about bacon and cheese???

Animal products sometimes taste great! But I don’t miss them much, because plant-based substitutes have improved significantly even in the short time I’ve been vegan. For bacon, I recommend Sweet Earth’s Benevolent Bacon, and for sliced cheese, either Chao or Follow Your Heart.

But these two substitutes alone don’t do justice to the cornucopia of great vegan food items, increasingly available at local grocery stores. If you’re just beginning to remove meat from your diet, and looking for the best drop-in replacements for existing recipes, the Gardein family of products is a great place to start:

And of course, for special occasions like today, there’s always the Tofurky Roast.

What about all the water it takes to make almond milk?

Almond milk has recently been under attack, and justifiably so, given the resources required for its production, and California’s fickle water supply. Thankfully, there are a plethora of other alternative milks, including soy, coconut, rice, and oat, each of which with its own advantages.

One quality all alternative milks have in common, however, is that they require less water per gallon to produce than cow’s milk. And, of course, none demand the sacrifice of a sentient being for their production.

What about plants, don’t they feel pain too?

Thomas Nagel famously said that “an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism.” While I argued earlier that there are common sense reasons to believe there is something that it is like to be an animal, the opposite can be said of plants.

For example, the biological machinery required to experience something like pain is evolutionary expensive. A given organism wouldn’t propagate those genes unless, like with humans, it made survival more likely. Moreover, feeling pain wouldn’t be biologically useful if the organism had no means of avoiding the painful stimulus. Therefore we should only expect to find the subjective experience of pain in beings that can move to avoid it (i.e. animals, but not plants).

With modern scientific techniques, we can do better than conjecture, and directly observe that plants do not have nociceptors, associated with pain response in humans and other animals, not to mention the complex neural structures likely required to process negative valence.

What about cultural traditions involving animal products?

This is a concern I mostly hear from the political left, and I believe it’s often well-intentioned. Wealthy, western, cisgendered, heterosexual, white men don’t exactly have a good track record of cultural sensitivity, to put it mildly. The fact that a disproportionate number of people advocating for animal rights currently fall into those categories should rightly set off alarm bells, and trigger a process of reflection within the movement.

But just as SJWs advocate for enlarging our moral circle to include those of different races, genders, abilities, and sexual orientations, the vegan movement seeks to also include other sentient beings, whose happiness and suffering are just as real as our own. This call to end speciesism is not a zero-sum attempt to divert attention away from other important causes; it’s a reminder that no movement towards liberation can be complete without animal liberation.

While we should respect the expression of cultural diversity as a foundational freedom and necessary good, where local traditions conflict with the wellbeing of animals (such as today’s festivities), we should affirm the fundamental right of sentient beings to exist free from deliberate harm.

What about people who rely on work in the animal agriculture industry?

It should come as no surprise that an industry built on the abuse of the animals in its care should do the same to its human employees. Jobs in animal agriculture are often filled by those most in need of the work, willing to expose themselves to hazardous conditions for low pay and few benefits. That these workers are often recent immigrants with varying legal status serves to suppress accident reporting and prevent unionization.

Like the animals they slaughter, these workers deserve better, from enforcement of existing labor protections, to a more equitable immigration system. What neither they nor anyone else deserves is a job that depends on the unnecessary suffering of sentient beings.

What about my cage-free, humanely raised, organic cricket flour?

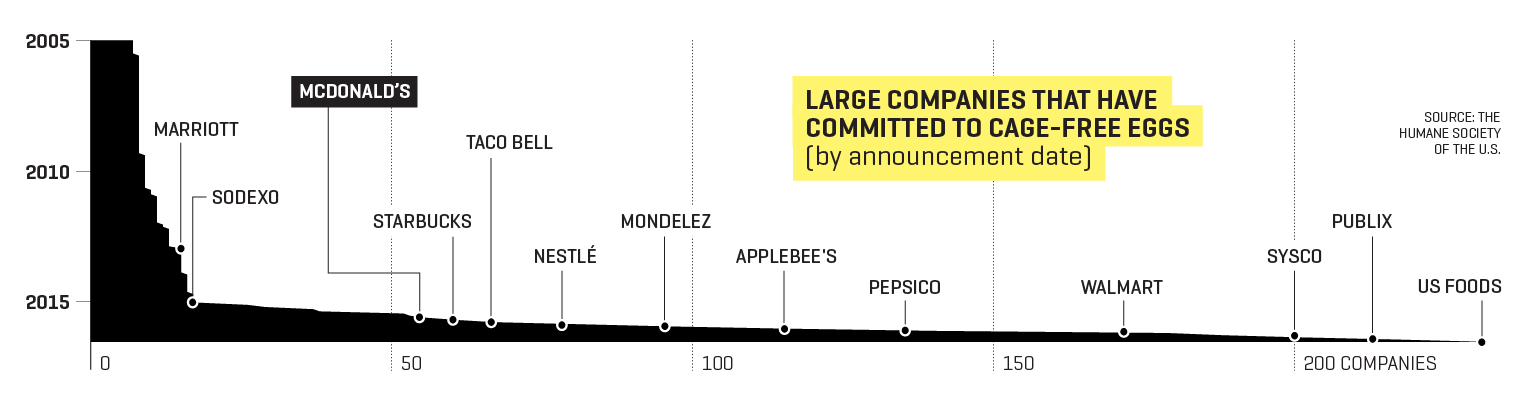

There have been signs of small improvements in the welfare of some farmed animals, with cage-free reform being the most notable success story. Because of the work of organizations such as Mercy For Animals and The Humane League, large companies like McDonald’s have pledged to transition to cage-free eggs, a move that could positively affect billions of hens every year.

But the promise of these “humane” animal products is offset by large downside risks. Incremental movements towards better farming techniques are often just a palliative salve on a mortal wound, soothing our own conscience more than the afflicted animals. To riff on Jeremy Bentham, the fundamental ethical question should not be “did they suffer less?” but “did they suffer?” And even in the best case scenario, once a farm animal does have a life worth living, what justification can there be to cut it short?

Organic products are often no better, appealing to nature while embodying all the myths of vegan elitism by encouraging ineffective, costly, and unsustainable agricultural practices. This criticism also applies to organic vegetables, grown on farms which eschew synthetic fertilizers and instead rely on manure from CAFOs, an eminently shitty reason for perpetuating animal cruelty.

Finally, I often get asked about the viability of food made from insects, such as cricket flour, as an alternative source of protein. Although there is room for debate within the vegan community, it’s my opinion that insects likely have some capacity for suffering, and so I avoid eating honey, cricket flour, and anything directly made by or from bugs. Also, gross.

It’s an unfortunate reality that, because of the necessity of pollination and the application of pesticides, few food products can claim to be completely cruelty free, including (but to a lesser degree) those found in most vegan diets. For now, the best we can do is to minimize our personal and collective harm, while supporting research into new technologies that might eliminate even insect suffering as a potential concern.

What about the farm animals that wouldn’t otherwise exist?

I recently attended a lecture with Jacy Reese, in support of his new book The End of Animal Farming. Although I was looking forward to his talk, I was most excited for the opportunity to ask him a question that had been bothering me since going vegan.

The problem with the end of animal farming is that it might also be the end of farm animals. Given what I’ve written about their welfare up to this point, this might seem like the best possible outcome, and I mostly agree. For instance, it’s almost certainly true that egg-laying hens, farmed fish, and Thanksgiving turkeys have a very low quality of life.

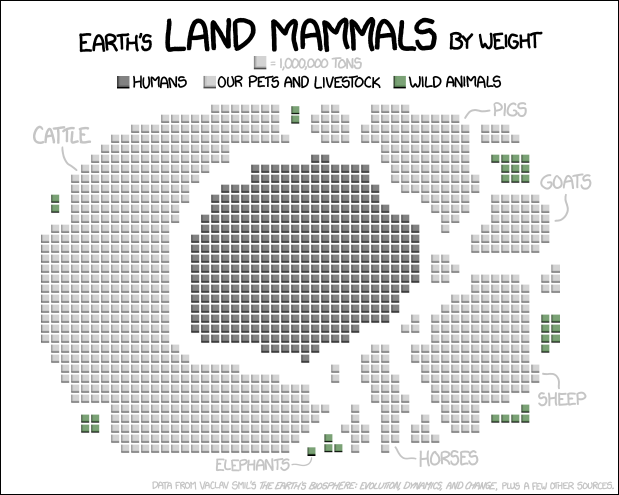

But my question hinged on a separate factor altogether, which is whether those (low quality) lives are still worth living. If the average Thanksgiving turkey would, on reflection, prefer existence to not, then my vegan diet has seemingly deprived a sentient being of its chance to experience a worthwhile life. And there are a lot of farm animals out there:

Even if this were a valid argument, however, it is not a defense of the status quo. Acknowledging the importance of turkey preferences is the first step on the slippery slope towards animal liberation. And, with the same resources we’re currently devoting to torturing animals for food, we could provide sanctuary and high quality lives to future generations of sentient beings, a fitting atonement for our many sins.

When I asked Jacy about this after his talk, I was heartened by his response; that the end of factory farming doesn’t represent the end of our relationship with animals, but could instead mark the beginning of new chapter in which they are finally treated in accordance with their preferences.