Mistake Theory Socialism

Earlier this year, while campaigning for mayor, Lori Lightfoot was subjected to a series of sharp criticisms from Chicago’s progressive community, mostly targeting her participation in the city’s various police reform initiatives. I reviewed a handful of these complaints and found them either lacking in substance or ungenerous in their interpretation of the available facts. At the time I compared these leftist anti-Lightfoot narratives to the right’s penchant for conspiratorial thinking, and fretted about the implications for the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

Since her landslide victory, Mayor Lightfoot has defied easy categorization, taking on Chicago’s deeply entrenched political establishment by curbing aldermanic prerogative, but also battling the Teachers Union (which endorsed her opponent) in contract negotiations that featured an 11-day strike. In an issue dear to my heart, she also paused water meter installations due to lead poisoning concerns (though no word yet on ranked choice voting).

The latest political skirmish has centered around her 2020 budget proposal, which passed city council this week by a 39-11 vote. Despite including some progressive victories such as a $15 minimum wage, the council’s socialist caucus represented six of the 11 dissenting votes, and this was indicative of a larger left-leaning backlash.

Some background

Before Rahm Emanuel was elected to his first term as mayor in 2011, Chicago ran 12 outpatient public mental health centers spread across the city. By the end of his second year in office, and after an $8 million cut in annual state funding, only six (below, in blue) remained.

At the time, Emanuel attempted to sell the consolidation to the public in two ways, claiming that “We’re not pulling back from service. In fact, we’re giving more service to more people and we’re adding a new benefit” while simultaneously touting $3 million in savings. Many patients and mental health advocates, however, weren’t buying it, and the resulting protests culminated in a brief occupation of the now-shuttered Woodlawn facility.

The closure of these six clinics became a defining part of Emanuel’s mayoral legacy, and the effort to reopen them persists nearly eight years later. And along with several other candidates in the 2019 election, Lightfoot made a campaign pledge to “reopen the mental health clinics that Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed in 2011 and invest an additional $25 million of city funds in mental health care.”

The criticism

My original Lightfoot Prospiracy post centered around a Slate Star Codex post about Prospiracy Theories, Scott’s attempt to co-opt the language and iconography of conspiratorial thinking to promote factual claims. This time, however, I’m reminded of his post on Conflict Vs. Mistake Theory, and in particular, the section on the nature of conflict theory:

What would the conflict theorist argument against the Jacobite piece look like? Take a second to actually think about this. Is it similar to what I’m writing right now – an explanation of conflict vs. mistake theory, and a defense of how conflict theory actually describes the world better than mistake theory does?

No. It’s the Baffler’s article saying that public choice theory is racist, and if you believe it you’re a white supremacist. If this wasn’t your guess, you still don’t understand that conflict theorists aren’t mistake theorists who just have a different theory about what the mistake is. They’re not going to respond to your criticism by politely explaining why you’re incorrect.

See, while Lightfoot’s 2020 budget falls short of her campaign pledge to reopen the six shuttered clinics, it does call for an additional $9.3 million in Mental Health Services, with which she intends to:

- Fund 20 public and nonprofit health centers to expand care in high-need neighborhoods, regardless of patients’ ability to pay or insurance status.

- Create violence prevention programming to address mental health needs in communities most impacted by violence and poverty.

- Invest in crisis prevention and response teams for people who have additional mental health challenges and have trouble accessing brick-and-mortar clinics.

- Coordinate the city’s mental health system to ensure every resident can access the care they need, where they need it, including an enhanced 311 helpline.

What would the conflict theorist argument against Lightfoot’s plan look like? Take a second to actually think about this. Is it similar to what I’m writing now - an explanation of Chicago’s recent history of mental healthcare, and a defense of how the six original clinics would actually provide better services than the 20 proposed by Lightfoot?

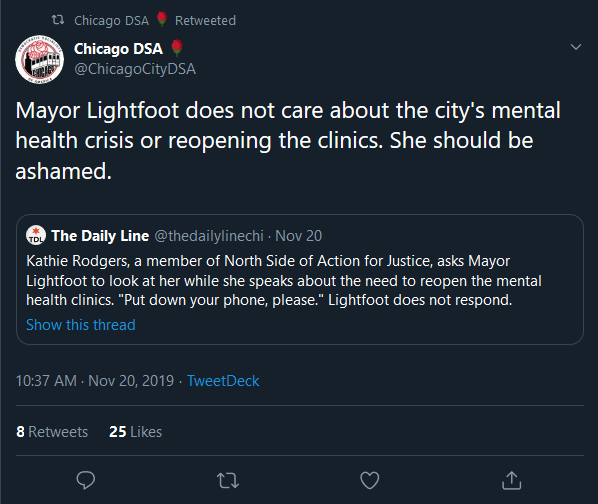

No. It’s “rose twitter” saying that Lightfoot doesn’t care about the city’s mental health, and was lying when she claimed she did during the campaign.

In more official circles, the progressive criticism of Lightfoot’s budget has been less needlessly inflammatory, but still features the reopening of the six clinics as a central theme. Which raises the question: what exactly would reopening these facilities entail?

Putting on a clinic

A primary argument from the “reopen” crowd is centered around the proximity of these clinics to the patients they served. A Tribune piece recounts the experience of one former patient, Jeanette Hanson, whose struggles to control her schizophrenia culminated in her 2014 death (having lost a family member to schizophrenia, this hits particularly close to home for me.)

Her case is both tragic and instructive. After the Beverly-Morgan Park clinic closed, Hanson was told to go to Roseland clinic, approximately three miles (or a 20 minute bus ride) away. But that “meant she had to take a bus ride through an area Hanson was afraid of, rationally or not, and she soon stopped going.” While she was certainly blameless for her inability commute, her experience does have strong implications for the distribution of clinics across the city needed to adequately serve patients with similar disorders.

Assuming Chicago is an approximately 10 mile by 20 mile rectangle, in order to make sure there is a clinic within approximately 1.5 mile radius of every patient like Hanson, Lightfoot would need to open at least 12 new clinics, in addition reopening the original six (though the math of covering rectangles with circles is surprisingly difficult!). (Note how similar this number is to her actual “20 public and nonprofit health centers to expand care in high-need neighborhoods” plan mentioned above.)

A second, darker observation about Hanson’s story is that, whatever the damage caused by closing the clinics, it’s mostly done by now. After eight years, arguments that still prioritize the routines of former patients are (in some cases tragically) outdated. They have likely found care elsewhere (or not), their preferred doctors have moved on (or retired), and even the majority of the buildings are now occupied by new tenants (click on the red markers in the map above).

From my perspective, the main question is this: if we were starting from scratch, would we open six identical clinics in the same locations as the ones closed in 2011? I’m not an expert in public health, city planning, political calculus, etc., but it seems plausible to me that, going forward, the best plan is one tailored to fit our current set of opportunities and challenges, not those from nearly a decade ago.

But what about the police?

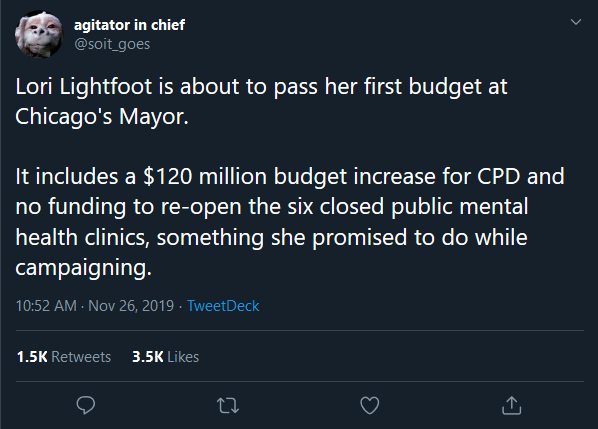

A second popular strain of criticism compares the increase in spending on police to the increase in mental health funding. Given their vociferous opposition to Lightfoot’s candidacy, it’s perhaps not surprising that activists like @soit_goes and Kelly Hayes continue to deride her as mayor. But is there any merit to this particular criticism?

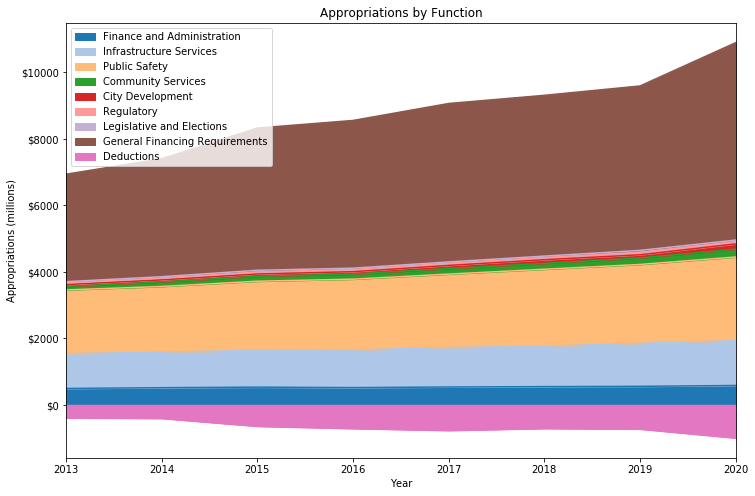

Whether or not Chicago needs such a large police force (even by the standards of comparable American cities) is a matter of some personal uncertainty, and probably outside the scope of this post. What is surprising, however, is how radical Lightfoot’s $9.3 million dollar increase in mental health spending is, relative to the small increase in the police budget. To get a sense for this, I took a deep dive into Chicago budgets dating back to 2013:

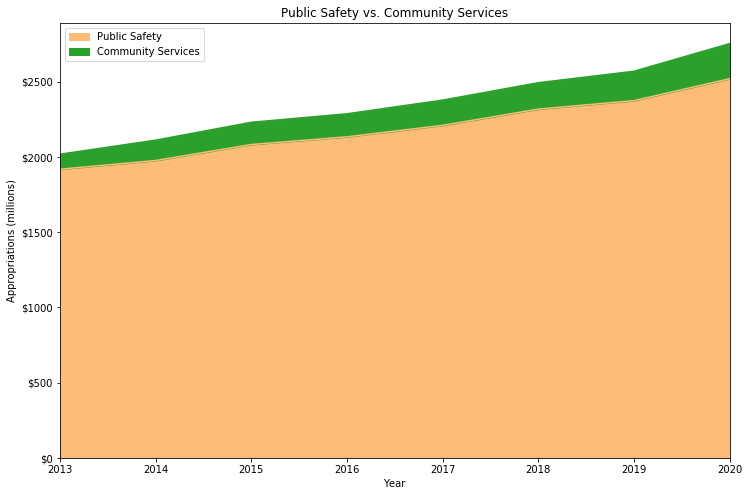

The above graph visualizes all “local” (non-grant) spending in Chicago. Removing functions like General Financing Requirements and Deductions gives a slightly better idea of where we put our money:

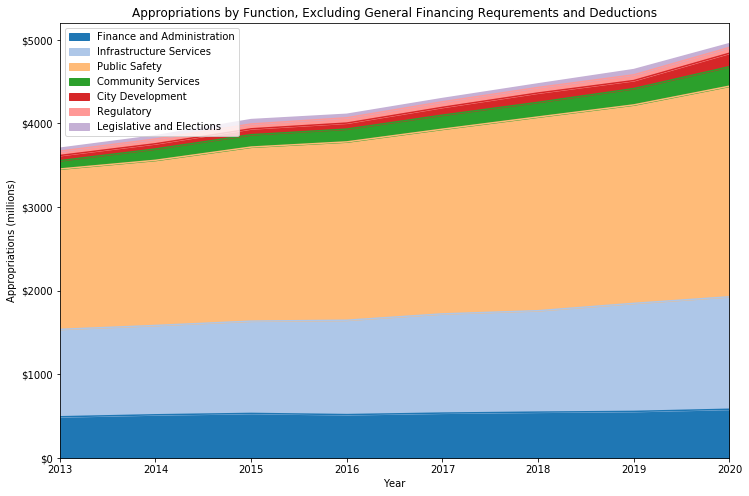

Spending is dominated by Public Safety (which incudes the Chicago Police Department), but besides a general trend of increasing appropriations, it’s still not clear if we can draw any conclusions about Lightfoot’s 2020 budget. Let’s zoom in on Public Safety and Community Services (which includes Mental Health Services):

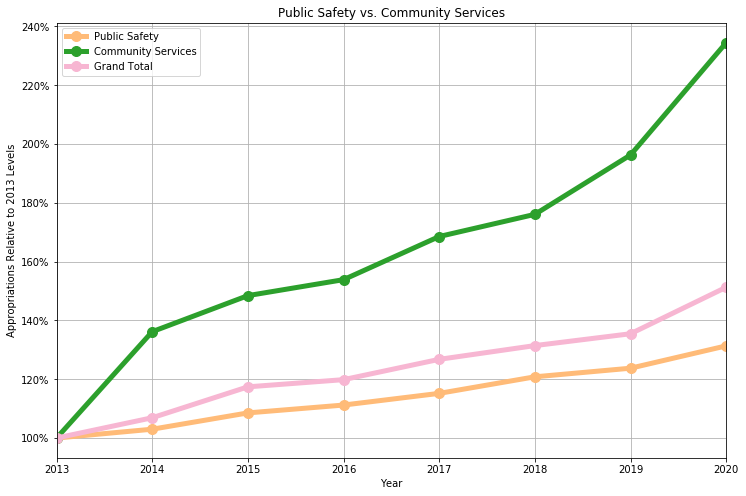

Public Safety and Community Services spending both increase in the 2020 budget, and because their scales are so different, you’d be forgiven for thinking there is nothing interesting to see here. But let’s instead compare spending in each function relative to 2013 levels:

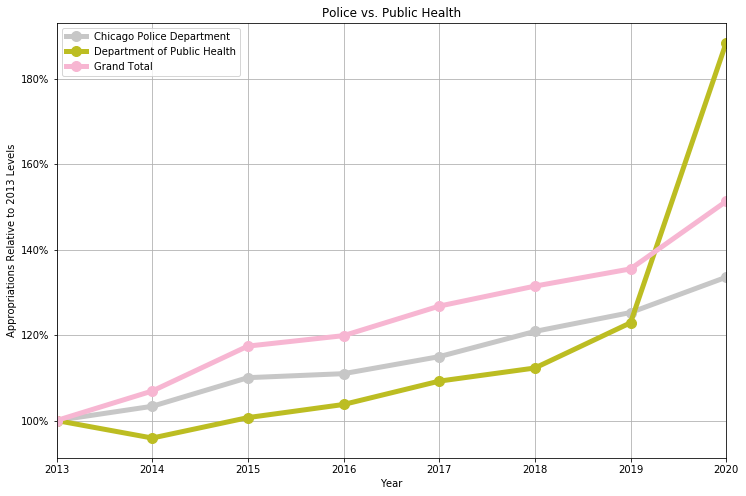

Here we can see that both Community Services and overall spending (Grand Total) have increased faster than Public Safety, with an especially sharp jump in 2020. Let’s use the same method, but directly compare the Chicago Police Department with the Department of Public Health, which oversees Mental Health Services:

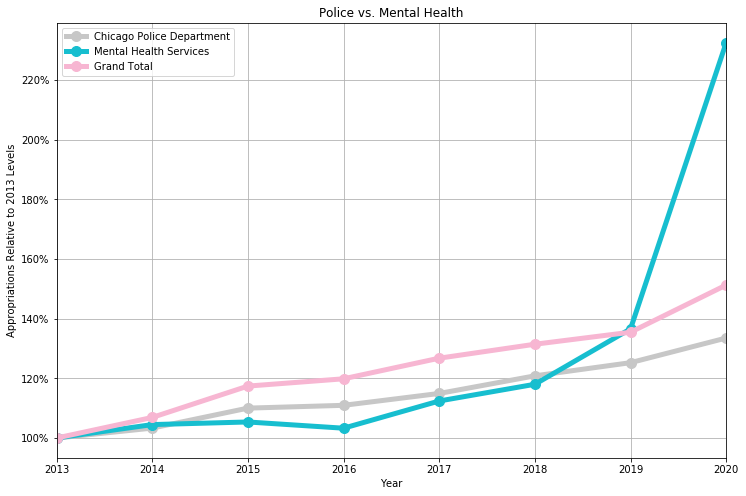

Based on this graph, the criticism of Emanuel appears justified, with public health spending lagging behind both general and police allocations for the entirety of his two terms. However, it’s clear that Lightfoot’s 2020 budget represents a drastic improvement, with a more than 50% jump in funding for the Department of Public Health. Narrowing in on Mental Health Services makes for an even starker contrast:

In fact, the 70% year-over-year increase in Mental Health Services is larger than any single-function spending increase in Chicago’s budget since my dataset began in 2013, and is much larger than the (apparently nominal) 6% increase in police spending. If this increase holds over the next two years of her term, she will have fulfilled the spirit of her pledge to increase mental health spending by more than $25 million, if not the actual promise to reopen six specific clinics.

Could Lightfoot have spent even more on mental health, and defunded a potentially bloated police force? Perhaps, but she could also have allocated the additional $9.3 million to the police, and any coherent political ideology should at least recognize the magnitude of this difference for the progressive victory that it is.

Closing thoughts

I dislike it when people use terms to describe what they’re not instead of what they are, but after covering two rounds of political controversies surrounding Lori Lightfoot, I want a term to at least describe the kind of progressive I aspire not to be. The closest I can come up with is “conflict theory socialist”, which is probably in the Authoritarian Left quadrant of the traditional political compass, or on top of John Nerst’s tilted political compass.

Lightfoot’s budget is the kind of incremental improvement that’s stereotypically eschewed by socialists, but it feels like more than just socialism that is driving her harshest critics, and conflict theory seems to explain the remainder of the variance. I think Lightfoot’s biggest mistake in this process was probably her initial, premature promise to reopen the clinics, which gave her political opponents fodder come budget time, but (if I’m right about conflict theory) had little chance of winning them over.

I’m not sure what force binds conflict theory and socialism so tightly (on Twitter, at least), but the term “conflict theory socialist” itself seems to imply a counterpart, the elusive “mistake theory socialist”. Since Nathan Robinson went off the rails this election cycle, however, I’m having trouble identifying any in the wild (on Twitter, at least). What would a modern mistake theory socialist even look like?

Maybe it’s Elizabeth Warren, who is currently suffering the political consequences of applying mathematical rigor to Sanders’s Medicare For All plan. Or maybe it’s the Effective Altruism movement, which applies consequentialist (rather than deontological) philosophy to enact “effective” social change. Or, ironically, maybe it’s even the Neoliberal Project, which advocates for many of the same social goals, but through policies like free trade, open borders, and carbon pricing.

So rather than say what I’m not, let me instead be the first to publicly identify as a “mistake theory socialist” (a term that currently returns zero search results!). And, uh, if you have any idea what that entails, please let me know.