Gamma Light

A recent episode of Radiolab covered a new technique for preventing plaque formation in the brain, a symptom correlated with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Although early forms of this treatment required gene manipulation and invasive surgery, an innovative concept involving only pulsed light at the gamma frequency proved to be equally effective in subsequent trials.

Human testing is still a ways off, but this gamma light treatment has the potential to help mitigate the most damaging symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, and at least one startup (founded by the researchers) is already aiming to capitalize. Unlike almost every other advanced medical procedure, however, any hobbyist can probably build a gamma light from parts they have sitting around the lab.

Don’t do this thing I’m about to do

Before we even start, let’s be clear that I’m not an expert in anything, let alone neuroscience, and that a reasonable person would absolutely not try to build or test one of these things on their own. Besides the obvious risk of seizures associated with any kind of strobing light in this frequency range, there is no evidence to indicate that this is an effective or safe treatment for anything that is not a laboratory mouse.

So if you are not a neuroscientist (or mouse), you should probably stop here. You’ve been warned.

Some background on gamma

If you don’t have access to the original article in Nature (and neither do I), the Radiolab epioside provides a good description of the experiment:

Since its discovery more than half a century ago, the gamma frequency has been the subject of a wide range of scientific speculation. Irregular gamma is correlated with neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, while strong gamma is associated with neural synchrony, and may even play a key role in the binding problem of conscious perception.

Beyond its natural manifestations, recent studies indicate that gamma can also be induced. Longtime practitioners of mindfulness meditation show increased gamma power, implying that brain rhythms may be receptive to training. And, as described in Radiolab, the brain resonates when exposed to light at the gamma frequency, either by way of genetically modified neurons, or even the visual system itself!

The design

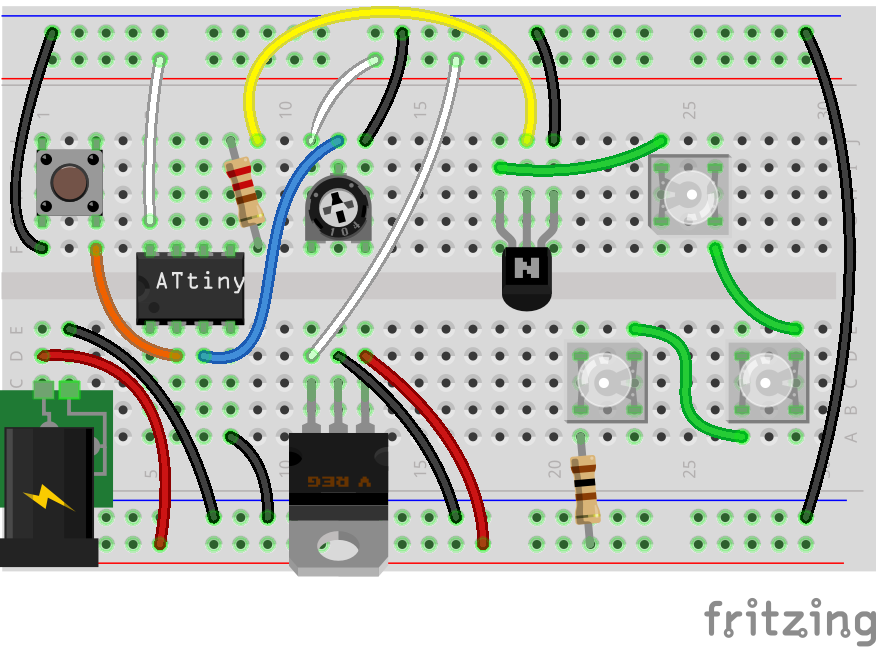

Despite the scientific complexity of the research, engineering a gamma frequency light is surprisingly easy. The objective, to flash an LED, is among the first examples in the official Arduino tutorials. I started building mine by laying out a breadboard, as shown below:

This design has a little added complexity, with an on/off momentary switch, trimpot for adjustable brightness, and transistor for driving extra current, but the basic principle is simple: the ATtiny85 processor outputs a 40Hz signal to control the LEDs.

I used a 12V DC supply from an old router as my high voltage rail, allowing me to drive several white (3.6V) LEDs in serial (but also necessitating the use of a separate 5V regulator for the micro). Though the transistor is overkill for a single LED chain (the ATtiny85 could sink the required 20mA), using one means increasing the brightness is as easy as adding more lights (up to the power limit of the supply).

A full parts list is shown here:

| Qty | Part |

|---|---|

| 1 | Small breadboard |

| 1 | ATtiny85 (or any Arduino-compatible micro) |

| 3 | White LED |

| 1 | Power plug |

| 1 | NPN-Transistor (PN2222A or equivalent) |

| 1 | 220Ω Resistor |

| 1 | 100Ω Resistor |

| 1 | 10kΩ Trimpot |

| 1 | Tactile switch |

| 1 | 5V Regulator (LM7805 or equivalent) |

The code

Like the electronics, the code is pretty straightforward. The only twist on standard Ardunio functionality is a basic software PWM function, which uses millis() to handle the signal generation, shown below:

int soft_pwm(unsigned long &start, int period, int duty) {

// calculate time difference from start

unsigned long diff = millis() - start;

// check for end of period

if(diff >= period) start = millis();

// check diff against duty

else if(diff >= duty) return HIGH;

return LOW;

}

The full project code is available here.

The light

Here’s the final product in action:

My phone’s camera aliased the gamma frequency a bit, but you get the idea. I find the light even fuzzier than Molly Webster reports in the Radiolab piece, and not in a good way. It’s pretty uncomfortable to look at directly, and it’s hard to imagine how it would feel in a room-scale application. Still, if the alternative was Alzheimer’s…