Do you believe in global warming?

I recently watched one of my favorite movies, Apollo 13, with my family over the holidays. After it ended, my aunt asked a seemingly reasonable question: if we went to the moon in the 1960s, why haven’t we been back in the last half century? After talking through some of the potential explanations for the decline of the American space program, however, it became clear that she was really asking: is there any reason to believe we actually went to the moon in the first place?

Questions like this are both annoying and illuminating. I believe we landed on the moon, to the extent that even debating the point seems like waste of everyone’s time. But what source can I call upon from within my parent’s living room to summon actual proof to support my claim? Clearly a grainy video wouldn’t be sufficient after watching a well-produced Hollywood reenactment, and I don’t have easy access to a sufficiently powerful laser to hit a retroreflector on the moon’s surface.

And some questions are just so broad that it’s difficult to know how to weigh the various factors. Yes, it is odd that we haven’t returned to the moon given our other technological advances, but what are the odds that a conspiracy the size of the space program could survive decades of scrutiny? What hope is there for rational discourse when it’s so difficult to agree on even the seemingly obvious?

Enter Rev. Bayes

A similar, but more relevant question popped up in a recent lunchtime conversation at the office. While everyone agreed in principle on the actions required to stem global climate change, a few coworkers refused to explicitly endorse human activity as the primary cause. My intuition was that this fit the description of a moon landing puzzle, and I had recently come across a neat mathematical tool which I thought might help resolve our disagreement: Bayesian networks.

Bayes’ Theorem, named after the 18th century mathematician and minister Thomas Bayes, is used for describing the probability of an event given relevant information. Julia Galef, host of the Rationally Speaking poscast, gives an excellent visual explanation in the following video:

Bayesian networks are just an extension of the basic theorem, where connected nodes represent the conditional probabilistic dependencies in the system. A great example of the concept is Brian Burke’s Deflategate model, which is pretty damning for Brady and the Pats.

Applying Bayesianism to a complex problem like climate change belief isn’t easy, and I’m not making the claim that this is anything more than armchair philosophy. But I do believe that Bayesian networks can amplify our intuition, much in the same way that night vision goggles extend our eyesight; by helping bring what was previously invisible within the range of human perception. Let’s see how they work.

Rising temperatures

The simplest Bayesian network has just two nodes, one for a hypothesis, and another for data. The hypothesis acts as a prior belief, or the probability that a given proposition is true. In the case of the climate change examples, GW represents the prior probability of the human-caused global warning hypothesis.

The data node represents information related to the hypothesis, which can then be used to update our belief, once measured. For climate change, let RT represent a “significant rise” in global temperatures. The two node network looks like this:

To assess the total probability of observing the data, we first have to set a prior probability for the hypothesis, then imagine the likelihood of observing the data under each possible outcome. As an example, let’s assume P(GW) = 0.1, representing a low initial belief in the existence of human-caused global warming. Estimating the probability of RT requires filling out the following table:

| Expression | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

P(RT|GW) |

0.90 |

Likelihood of rising temps if human-caused global warming is real |

P(RT|-GW) |

0.20 |

Likelihood of rising temps if human-caused global warming is not real |

These estimates capture the high likelihood (0.90) of rising temperatures in the event of human-caused global warming, and the small but non-zero likelihood (0.20) that temperatures would rise regardless.

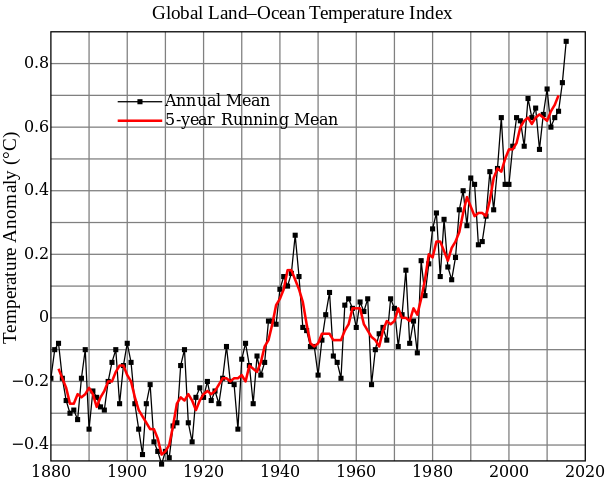

Next, we need to observe the data. NOAA recently reported that 2016 was the warmest year on record, the third straight record breaking year. This fits “nicely” with the global trend since the beginning of the industrial revolution, visualized in the following graph:

Those sure look like rising temperatures to me. Finally, we can use this observed data to update our prior by calculating P(GW|RT), or the probability of human-caused global warming given significantly rising global temperatures. Bayes makes this easy - just plug it into the formula P(GW|RT) = P(RT|GW)*P(GW)/P(RT)! (Note that P(RT) = P(RT|GW)*P(GW) + P(RT|-GW)*P(-GW))

After observing rising temperatures, our posterior belief in human-caused global warming is approximately 0.33; not yet credible, but still an improvement on our prior of 0.1.

Scientific consensus

A two node model is fine for demonstration purposes, but adding an extra node can show the power of Bayesian networks as an intuition multiplier. In the climate change model, let’s add a second piece of evidence, SC, representing the consensus among climate scientists in the reality of human-caused global warming. Since the scientific process uses observed data (RT) to make inferences about hypotheses (GW), SC is related to both of the previous nodes as shown in the following network diagram:

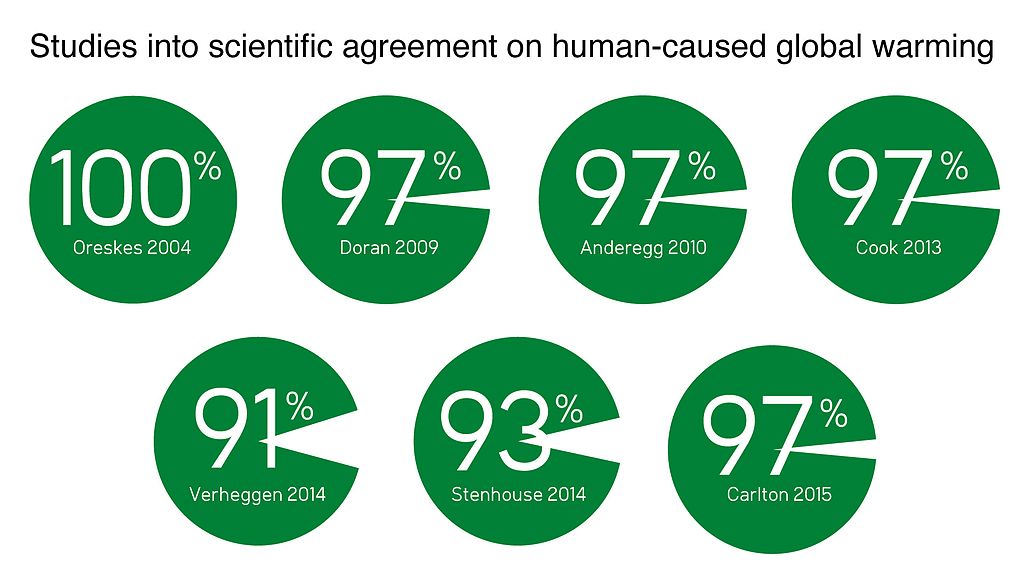

Because of the public nature of the debate, the scientific opinion has been well documented: over 90% of climate scientists agree on the reality of human-caused global warming.

The full network

Now that the network is connected, the last remaining step is to assign probabilities for each parameter. Use the sliders below to set the values, and see how they affect the posterior belief in GW.

P(GW) =

This represents the prior probability of human-caused global warming. Although concern about the increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide were raised as early as the 1890s, it wasn’t until after WWII that the idea was taken seriously. Imagine what probability you would assign, knowing only what information was available at the beginning of the industrial revolution.

P(RT|GW) =

Now imagine that you’re shown the above graph of rising temperatures throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries. If human-caused global warming is real, what is the probability of observing such a significant temperature increase?

P(SC|RT,GW) =

Given that temperatures are rising and global warming is real, what’s the probability that climate scientists would correctly form a consensus around that belief? This should account for the fact that even the most accepted scientific theories, like evolution, have some skeptics.

P(RT|-GW) =

Assume for a moment that human-caused global warming is not real - what is the probability that global temperatures would be significantly rising regardless? This should account for both the probability that the temperature increase is an anomaly, and also that the earth is warming for non-anthropogenic reasons.

P(SC|RT,-GW) =

Given that human-caused global warming is not real, but the global temperature is rising, what are the odds that scientists would incorrectly identify human activity as the cause for the increase?

P(GW|RT,SC) =

This represents the posterior belief in human-caused global warming, given the reality of rising temperatures and scientific consensus. Depending on how you set sliders, this is likely higher than the prior probability, indicating that the observed evidence supports the initial hypothesis.

(For reference, the expression for the final calculation is P(GW|RT,SC) = P(SC|RT,GW)*P(RT|GW)*P(GW)/(P(SC|RT,GW)*P(RT|GW)*P(GW) + P(SC|RT,-GW)*P(RT|-GW)*P(-GW)))

Future considerations

I workshopped this example around the office and got some good (albeit not universally positive) feedback. One coworker pointed out that the P(RT|-GW) is vague because it includes not only the scenario where there the rising temperatures are anomalous, but also the possibility of non-human-caused global warming, due to a natural (but undetected) mechanism. Another noted that the closer to equal you set the factors (representing a wholly skeptical position regarding the available evidence), the more weight your (somewhat arbitrary) prior carries.

Beyond these valid criticisms, the human-caused global warming example is problematic because most people (or at least those who might be convinced by an abstract mathematical argument) are already aware of the evidence I presented, and have likely already factored it into their prior. In that sense, this technique is more useful as an ongoing thought exercise, where the probabilities (and the network itself) are continuously updated to reflect the best available evidence.

Finally, while researching this post, I came across a recent paper highlighting a significant limitation of networks with three nodes or more: there are certain configurations that can produce divergent beliefs after observing the same evidence. This could potentially give both sides cover if a situation produces contrary belief, and makes the whole rationality thing seem a little hopeless.

Still, I think Bayesian networks are a good tool to have in the bag when confronting difficult problems, and could at least help converge on what’s specifically causing us to diverge.