A Modest Proposal

While at EA Global 2016, I met a fellow attendee who was in the process of donating a kidney to a stranger. Despite altruism being the theme of the conference, with most talks focused on how best to donate money to worthy causes, this struck me as an absurdly generous plan. I believe that sharing excess wealth to help others is a kind of moral obligation, but giving up a seemingly essential body part seems like another thing altogether.

She patiently explained to me that living donation is a relatively routine procedure, with few long term consequences, and a low probability of post-op complications. Her home state of California even requires employers to grant donors an 30 days of paid leave for recovery. And because of kidney chains (waiting pairs of willing but non-matching donors and recipients), a single altruistic donation can start a domino effect that ends up saving dozens of lives.

Although I still have both my kidneys (at the moment), I found this story compelling enough to do some research after the conference, and I shall now therefore humbly propose my own thoughts, which I hope will not be liable to the least objection: let’s enact government-mandated kidney donation.

- Kidneys as a right

- Econs v. humans

- Choice as a more fundamental right

- And while we’re on abortion

- In summary

Kidneys as a right

I’m not the first to propose a form of universal kidney donation. Current Affairs magazine editor Nathan Robinson laid out this plan in a 2015 article:

The system would be roughly as follows: kidney duty would operate like jury duty, a responsibility of citizenship. Individual citizens would be selected at random to be kidney donors, though exemptions could be offered based on age and health. Each person would have an equal likelihood of becoming a donor, with every person on the waitlist being matched with a random mandatory donor. In this way, four thousand lives per year would be instantly be saved.

In addition to citing the obvious example of jury duty, Robinson also draws parallels with military conscription, likely a far riskier (and potentially morally dubious) way of using your body to save the lives of your fellow citizens. Not only is kidney donation a noble act (imagine how good it would feel to save a friend’s life), the converse is also true. Again, from Robinson:

At the personal level, it is almost certainly morally indefensible for an individual not to donate his or her kidney. After all, a life is saved at relatively little cost to one’s self.

Econs v. humans

If you haven’t already guessed from the title, this post isn’t really about universal kidney donation (though I still think it might be a good idea!). Instead, it’s about the uncomfortable feeling I had at the conference, and that I tried to convey with the above proposal. Why is it that an individual kidney donor is celebrated as a hero, but a mandated kidney donation program produces so much angst?

Partly, I think this can be explained by recent research in behavioral economics. Dan Ariely, an psychology professor at Duke University, has run several experiments demonstrating the difference between social and market norms. From his book Predictably Irrational:

The fact that we live in both the social world and the market world has many implications for our personal lives. From time to time, we all need someone to help us move something, or to watch our kids for a few hours, or to take in our mail when we’re out of town. What’s the best way to motivate our friends and neighbors to help us? Would cash do it — a gift, perhaps? How much? Or nothing at all? This social dance, as I’m sure you know, isn’t easy to figure out — especially when there’s a risk of pushing a relationship into the realm of a market exchange.

When we push kidney donation from the social to the market (or in this case government) realm, we change the meaning of the act from a selfless gift to a literal “pound of flesh”, even though the end result is the same. The feeling we get when our good deeds are undervalued (or mandated) helps to explain our reluctance to impose a beneficial program like universal kidney donation, but I don’t think it’s whole story.

Choice as a more fundamental right

During the 2016 election, I was disappointed to learn that a handful of friends, family members, and coworkers were supporting Trump despite a mountain of disqualifying behavior. Particularly disturbing among them was my grandmother, who was made in the Mr. Rogers mold, and is the most consistently kind person I know. Of all the perplexing things to come out of the election, this one has bothered me most - how is it possible that someone like her could support something like this?

I asked her a nicer version of that question when I saw her over the holidays, and was surprised to learn that her vote swung on a single issue: abortion. Even though this was the first time I’ve ever heard that word mentioned in a family conversation, I could have guessed there would be strong feelings about the subject: my dad’s immediate family has three nuns and a deacon, at last count.

As a liberal adult with a Catholic upbringing, my views on abortion have changed significantly over time, and until recently, my stance was that “reasonable people can disagree”. I still believe that’s mostly true, but thinking about kidneys has pushed me over the edge into the pro-choice camp because the two issues share the following social norm:

You can’t force someone to risk their life to save another person’s life

One of the hardest things about understanding the abortion issue as a man is the difficulty putting myself in the position of a pregnant woman. From an outside perspective, it can be a simple equation: there are two lives at stake (mother and child), and just because the necessary equipment for keeping one alive (the womb) happens to be inside of the other is irrelevant - both lives should be saved.

But read that sentence again, substituting [mother, child, womb] for [donor, patient, kidney], and you’ll see what I’m getting at. If you don’t think the two are comparable, consider the following:

- Giving birth and kidney donation have a similar mortality rate (18:100K to 30:100K).

- Donation has fewer longterm complications than pregnancy.

- Being forced to carry a baby conceived as a result of rape is the rough equivalent of waking up in an ice-filled bathtub short one kidney (which apparently isn’t even a thing).

Maybe it’s still good to save the child/patient’s life, but chances are that, like me, you still have both your kidneys.

And while we’re on abortion

Aside from choice, there’s another confusing aspect to my grandma’s vote: why does she believe that Trump will decrease the number of abortions? Based on rhetoric alone, Trump’s position on this issue (and everything else) has been incoherent. Clinton, on the other hand, was a consistent advocate throughout her career for making abortions “safe, legal and rare”. Though their methods differ, both parties seem to agree that reducing the number of abortions is a good thing - so why the conventional wisdom that Republicans have better pro-life policies?

Like many consequential issues, it’s impossible to run a true RCT on abortion policy, because a proper control group would be another United States. However, smaller experiments have been happening at the state level in the decades since Roe v. Wade, and it is possible to make some inferences. A recent study by the Guttmacher Institute showed that the US abortion rate is at a record low, and that change is largely attributable to the decline in unintended pregnancies, due in part to increased access to contraception through the Affordable Care Act.

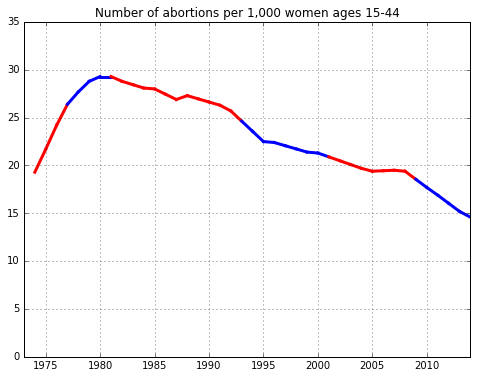

The report included a graphic of the declining abortion rate, which I’ve colored to represent the president’s political party.

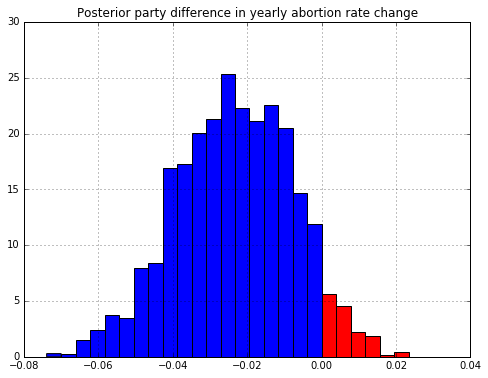

At a glance this shows that, while the abortion rate has been declining overall since the early 80s, the change has been slightly faster under Democratic leadership. To test this theory, I analyzed the data using Bayesian estimation and got the following results:

The above graph shows the difference in the average change yearly in abortion rate between the two parties. Without making any causal inferences, the data indicate that abortion rate is about 93% likely to decline more under a Democratic administration than a Republican one. Go figure.

In summary

In Peter Singer’s Expanding Circle essay, he poses the following thought experiment:

To challenge my students to think about the ethics of what we owe to people in need, I ask them to imagine that their route to the university takes them past a shallow pond. One morning, I say to them, you notice a child has fallen in and appears to be drowning. To wade in and pull the child out would be easy but it will mean that you get your clothes wet and muddy, and by the time you go home and change you will have missed your first class.

I then ask the students: do you have any obligation to rescue the child? Unanimously, the students say they do. The importance of saving a child so far outweighs the cost of getting one’s clothes muddy and missing a class, that they refuse to consider it any kind of excuse for not saving the child. Does it make a difference, I ask, that there are other people walking past the pond who would equally be able to rescue the child but are not doing so? No, the students reply, the fact that others are not doing what they ought to do is no reason why I should not do what I ought to do.

I find this extremely compelling, but I’m also troubled by the unasked question: if it’s a moral act to save the child, is it morally indefensible not to? If yes, would that change my position on abortion? What exactly should I do with this extra kidney?

It’s also possible this none of this really gets at the heart of my grandma’s position. Abortions likely decrease more under Democrats, but Republicans might share her values on issues like contraception, and would better represent her views on a host of other issues. The abortion issue might just be a proxy for all of our intractable disagreements; a depressing thought.

However, I’m optimistic about the prospect of bridging (some of) our divides, starting with mutual reflection on the tough issues. Your move, grandma.