Hold the Reins

Edit 2019-08-12: After listening to Jeremiah Johnson and Rob Wiblin discuss kidney donation on the Neoliberal Podcast, I decided to revise this post with a few moderate updates.

I follow thechicrew (a vegan microsanctuary) on Instagram mostly for the cute animal pics, but lately an unrelated storyline has been developing on their feed. One of the caretakers, Jay, recently donated a kidney to an unknown 14-year-old recipient. From the announcement post:

Kidney disease is the 9th leading cause of death in the U.S., more common than breast or prostate cancer deaths. It seems painfully obvious to me that those who can donate SHOULD. I know Jay has inspired me to see if I’m eligible and if you’re also inspired, you can learn more at kidney.org. ❤

Jay’s is not the first altruistic kidney donation I’ve encountered. Peter Singer made the case for kidney donation in his 2013 TED Talk, Dylan Matthews documented his own donation process on Vox’s Future Perfect podcast, and I even met an altruistic donor myself at EA Global 2016.

These stories have been an inspiration to me, and as a result I’ve been strongly considering living donation. But “Doing Good Better” asks us to look beyond mere inspiration and consider the aggregate impacts of our actions. Is it really “painfully obvious” that “those who can donate SHOULD”? Let’s do the math.

Recipient outcomes

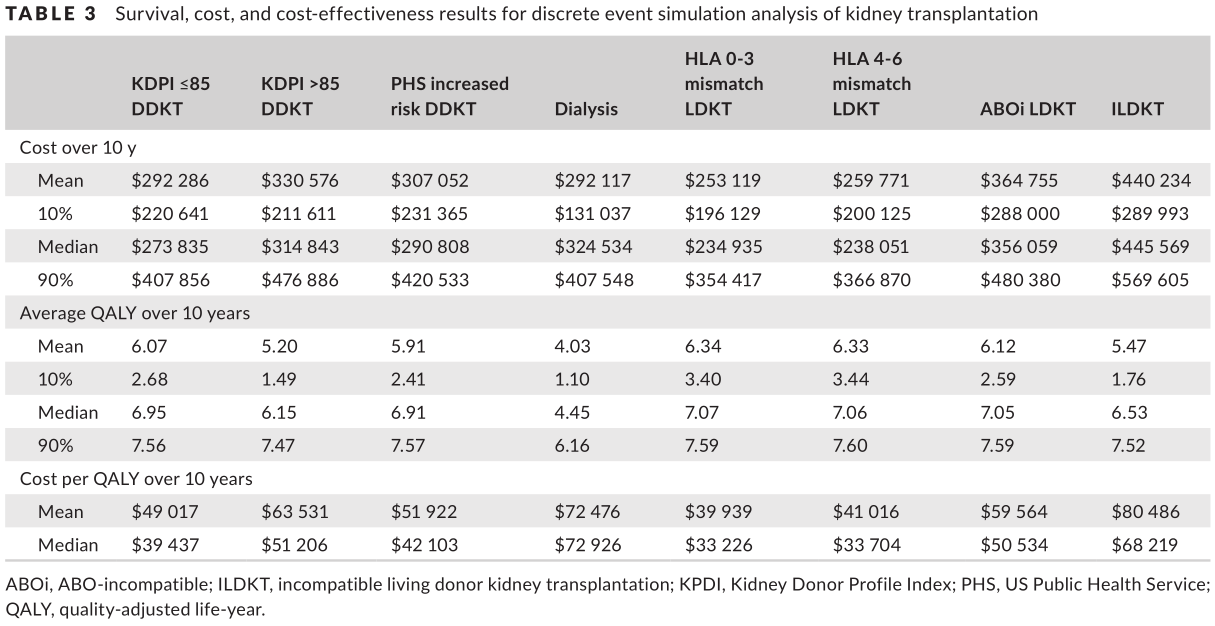

To quantify the benefits of kidney donation, I used numbers from “An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice”, which uses a Markov model simulation of recipient outcomes in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) to generate the following table:

In the ideal case, the two columns of interest are “HLA 0-3 mismatch LDKT” (a living donor kidney transplant with a the minimal number of human leukocyte antigens mismatches) and “Dialysis” (a non-transplant therapy to replace kidney function). Using the “Average QALY over 10 years” row, transplanting a kidney from a living donor to a dialysis patient will realize a median benefit of 7.07 - 4.45 = 2.62 QALYs.

The 10 year time horizon is not unreasonable, but given that donated kidneys last an average of 15 years, let’s multiply by a factor of 1.5 to get a total benefit of around 4 QALYs.

Donor outcomes

This benefit comes at a cost, however, since the donation procedure is not without risk. As with any major operation, there is a small chance of perioperative death, affecting approximately 3 in every 10,000 donors.

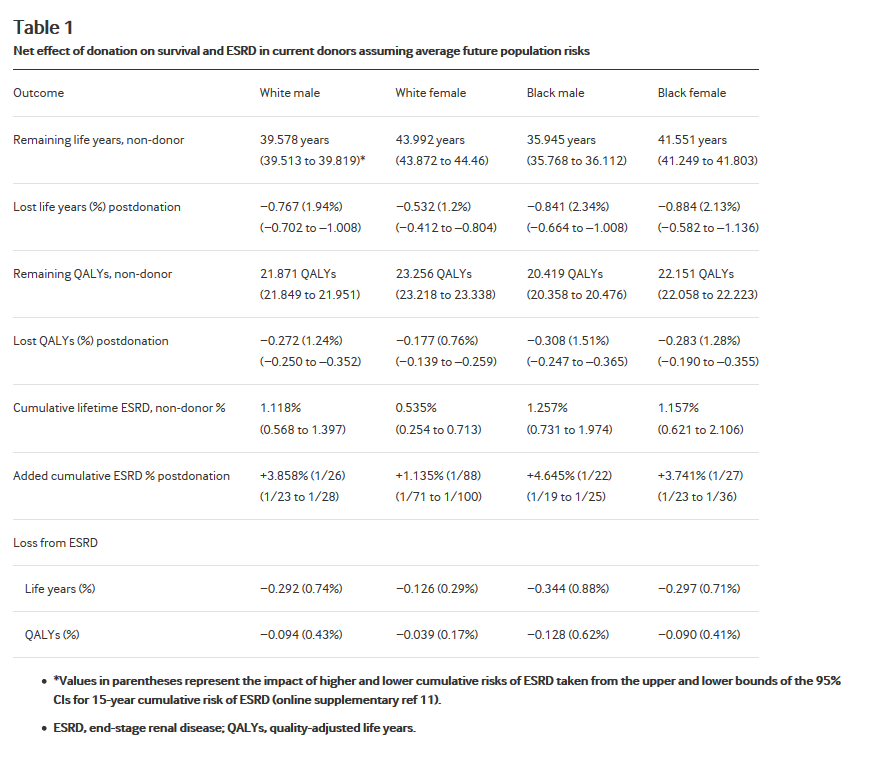

But there are other concerns as well. Even healthy kidney donors become slightly more prone to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), as described in “Lifetime risks of kidney donation: a medical decision analysis”. The paper, which also used a Markov model, simulated outcomes for 40-year-old donors of varying race and gender:

For the typical white, male 40-year-old, kidney donation results in a loss of approximately 0.272 QALYs, or 1.24% of the remaining quality years. Adding in the small probability of immediate death (3/10,000*21.871), and adjusting for my current age (35), I’ll round this number up to approximately 0.3 QALYs lost.

Non-kidney donations

On the surface then, living kidney donation does seem like the “painfully obvious” choice, since the procedure generates an average of 4 QALYs of benefit for recipient and costs only 0.3 QALYs to the donor, for a net benefit of 3.7 QALYs. The picture gets murkier, however, when non-kidney donations are included. Consider the following:

- Giving What We Can (GWWC) is an Effective Altruism (EA) organization which encourages members to donate 10% of their earnings to effective charities. Over the 10 years since its inception, they have tracked $126,751,939 in donations from their 4,210 members, for an average yearly donation of

$126,751,939/4,210/10 =~ $3,000per member. Note that this estimate is likely conservative, since some members (like me!) don’t use the GWWC site to track their donations. - GiveWell, another EA organization, reviews giving opportunities and provides a yearly list of the most cost-effective organizations. In 2018 they estimated that The Against Malaria Foundation (AMF) prevents the death of an individual under the age of 5 (through the distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets) for every $3,070 donated, using “conventional” assumptions.

- In a separate document, GiveWell Senior Research Analyst James Snowden calculated that averting the death of an individual under the age of 5 is worth 42.7 wellness-adjusted life years (WALYs, a more comprehensive version of QALYs that includes non-health states). However, in order to make this more directly comparable to the QALY numbers above, I’ll use only the “WALYs lost because of direct badness of death” portion, or 31.2 “QALYs”.

- Finally, in addition to donor QALY losses, the “Lifetime risks” paper also calculates that the average white male 40-year-old will lose 0.767 years of life through the donation process. I’ll round this up to 1 year given the considerations listed in the previous section.

Putting it all together, one year of a GWWC member’s life represents a $3,000 gift to an effective organization like AMF, which saves the life of a 5 year old for every $3,070 donation, for a average benefit of about 1*3,000/3,070*31.2 = 30.5 QALYs! Or stating it another way, living kidney donation actually costs effective altruists up to (3.7 - 30.5 =) 26.8 QALYs through lost monetary donations.

Conclusion

Since not everyone is an effective altruist (yet), living kidney donation still seems like a good idea for most people. Jay has no regrets despite a difficult recovery process, Dylan Matthews seems to have had a positive experience, and other donors from within the EA community have ideas for making the procedure even more beneficial.

There’s even the possibility that your non-directed donation could start a kidney chain, with cascading benefits that may reverse the above conclusions.

If it’s not for you, however, that’s fine too. But do consider joining GWWC regardless. As Slate Star Codex notes in Nobody Is Perfect, Everything Is Commensurable:

Nobody is perfect. This gives us license not to be perfect either. Instead of aiming for an impossible goal, falling short, and not doing anything at all, we set an arbitrary but achievable goal designed to encourage the most people to do as much as possible. That goal is ten percent.

Everything is commensurable. This gives us license to determine exactly how we fulfill that ten percent goal. Some people are triggered and terrified by politics. Other people are too sick to volunteer. Still others are poor and cannot give very much money. But money is a constant reminder that everything goes into the same pot, and that you can fulfill obligations in multiple equivalent ways. Some people will not be able to give ten percent of their income without excessive misery, but I bet thinking about their contribution in terms of a fungible good will help them decide how much volunteering or activism they need to reach the equivalent.

Update

Living kidney donation has been a hot topic on my newsfeed recently, following Jeremiah Johnson’s donation and some corresponding Neoliberal Twitter buzz:

After doing a little follow-up research, I wanted to expand on a few points that deserved more consideration in my original post.

First, I recommend reading Tom Ash’s entry in the Effective Altruism Forum, “Kidney donation is a reasonable choice for effective altruists and more should consider it”. As you might expect from the title, Tom arrives at essentially the opposite conclusion, but with a more thorough (albeit potentially outdated?) analysis. The crux of our disagreement stems from the way we adjust for the reduced life expectancy of living donors. Tom provides a few calculations to show that the financial effects of mortality and ESRD are negligible, and argues that since any ensuing health risks are likely decades away, uncertainty (over “retirement, technological improvement, ability to receive a transplant, and defection from the EA cause”) swamps other considerations.

Although the reasoning here is interesting, I’m not sure it’s enough to shift the balance on its own. My calculations imply that typical EA giving for one additional year does an order of magnitude more good than kidney donation, in QALY terms. To even the outcomes is to assume that 90% of the value of an additional year of life is somehow lost, potentially through one of the four factors Tom lists. I think(/hope) that the most likely of these is technological improvement, which in itself might be a good reason to consider donating immediately (while there are still QALYs to be had)!

Second, I’d be more persuaded that living donation is worth the risk if I was confident in the ex-ante expected length of the kidney chain I was starting. I contacted NKF and UNOS about this, and eventually got the following response:

Unfortunately there is no way to determine how long a chain will be prior to entering a KPD program. Even after a chain is found, there is no way in advance to determine if the entire chain will proceed to transplant, it will suddenly end with 1 or 2 transplants, or how long it may continue on for X number of additional transplants.

All that being said, my opinion on living donation is shifting from “probably not worth it” to “maybe not a bad idea.” As the tweets I linked to above imply, there might be good non-QALY reasons for donations, such as capturing the moral high ground for future debate (only sort of kidding). In part to gather more information, I’ve started the donor screening process, and will likely post another update here soon.