Solar Fan

While bednets have been immensely successful as a life-saving intervention for Malaria, some problems remain. Although allegations of improper use seem more anecdotal than evidenced-based, the issue of non-use (despite net availability) does likely increase the risk of transmission and death. The most commonly reported reason for non-use is discomfort due to heat, unsurprising given the restriction in airflow due to the tight mesh, and the predominately equatorial climate where the disease thrives.

In this post I’ll share my work towards a technological solution to this problem: a solar powered cooling fan that can be placed inside the net.

- Background on malaria and ITNs

- Heating and cooling

- So why make another one?

- The solar fan (needs a catchier name)

- Money, it’s a hit

- Future plans: wind light?

Background on malaria and ITNs

Despite being a preventable and curable disease, Malaria killed close to 500,000 people and sickened another 200 million in 2015. The majority of these cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and children under the age of five account for more than 70% of the fatalities. Vulnerable groups such as pregnant women, patients with HIV/AIDS, and immigrants who lack natural immunity are also disproportionately affected.

However, despite the bleak statistical picture, there is reason for hope. According to the WHO:

Between 2000 and 2015, malaria incidence among populations at risk fell by 37% globally; during the same period, malaria mortality rates among populations at risk decreased by 60%. An estimated 6.2 million malaria deaths have been averted globally since 2001.

A major development responsible for the decline of Malaria has been the widescale distribution of insecticide-treated bednets (ITNs), which help to prevent transmission by mosquito during the night. The number of children sleeping under an ITN in sub-Saharan Africa has increased from 2% to 68% over the same time period, thanks to large net distributions by organizations like The Against Malaria Foundation.

Heating and cooling

One major drawback of ITNs is the lack of air circulation due to the tightness of the net’s mesh. According to a recent study, the discomfort due to heat accounts for nearly half of the reasons given for unused nets. Given the meteorological correlation between warm climates and sunshine, and the recent decline in the cost of solar power, a natural conclusion would be to develop a solar powered cooling device to encourage ITN use (increased airflow might itself also be a mosquito deterrent).

In fact, this idea has been proposed several times in the last few years. Olivier J.T. Briët’s 2012 paper in MalariaWorld Journal describes the need for exactly such a device, and he proposes several additional useful features such as a mounting stand, reading light, and phone charger. The Green World Health Net took the concept a step further with the Boko project, building a prototype fan and conducting a pilot study in rural Ghana.

So why make another one?

While it’s great that there are already active developments in this area, I think a more open approach could help solve the problem of ITN cooling even faster. Green World Health Net has taken a commendably sustainable approach, designed to minimize the amount of parts sourced from abroad. But optimizing for sustainability at the level of solar panel construction is likely inefficient (especially given recent pricing trends). It’s also difficult to find even a picture of their prototype, let alone any technical details about the product.

My design for the solar fan takes a different approach, utilizing the efficiency of existing manufacturing specialization, while maintaining an open source philosophy. All of the electronics and software design files can be found here, meaning that anyone can learn how it works and make their own.

The solar fan (needs a catchier name)

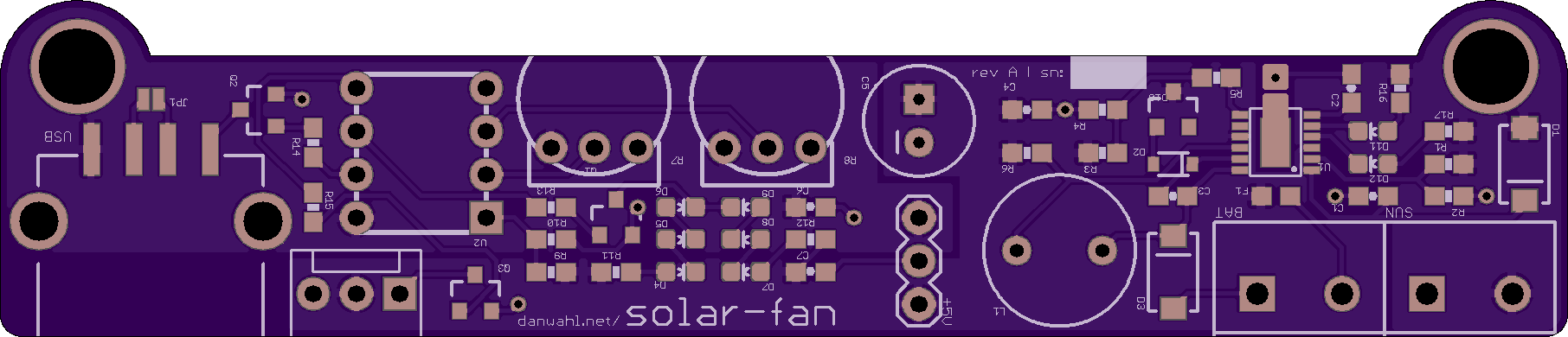

At the heart of the solar fan is a custom printed circuit board (PCB), which integrates both the charging and fan control circuitry, and attaches directly to the bottom of a standard 92 mm computer fan. In addition to the fan, the PCB supports a built-in LED light array, and an optional USB port for phone charging. The outputs for the fan, light, and USB charger are controlled by two rotary dimmers and a microprocessor running Arduino firmware (more on this below). A rendering of the prototype PCB is shown here:

The most interesting (and expensive) feature is an on-board LT3652, a battery charging module which provides peak power tracking (MPPT) to keep the solar panel at its most efficient voltage. This IC allows for a wide range of potential solar panel and battery options, with input capability of 32 Volts and charging current up to 2 Amps.

An ATtiny85 processor measures the two rotary dimmers (for the fan and lights) and battery voltage, and controls the fan, LEDs, and USB charger through transistors. The Arduino-based firmware simply sets the fan and light outputs to the corresponding dimmer setting, checks for low battery conditions (in which case all outputs are disabled), and otherwise stays in low power mode.

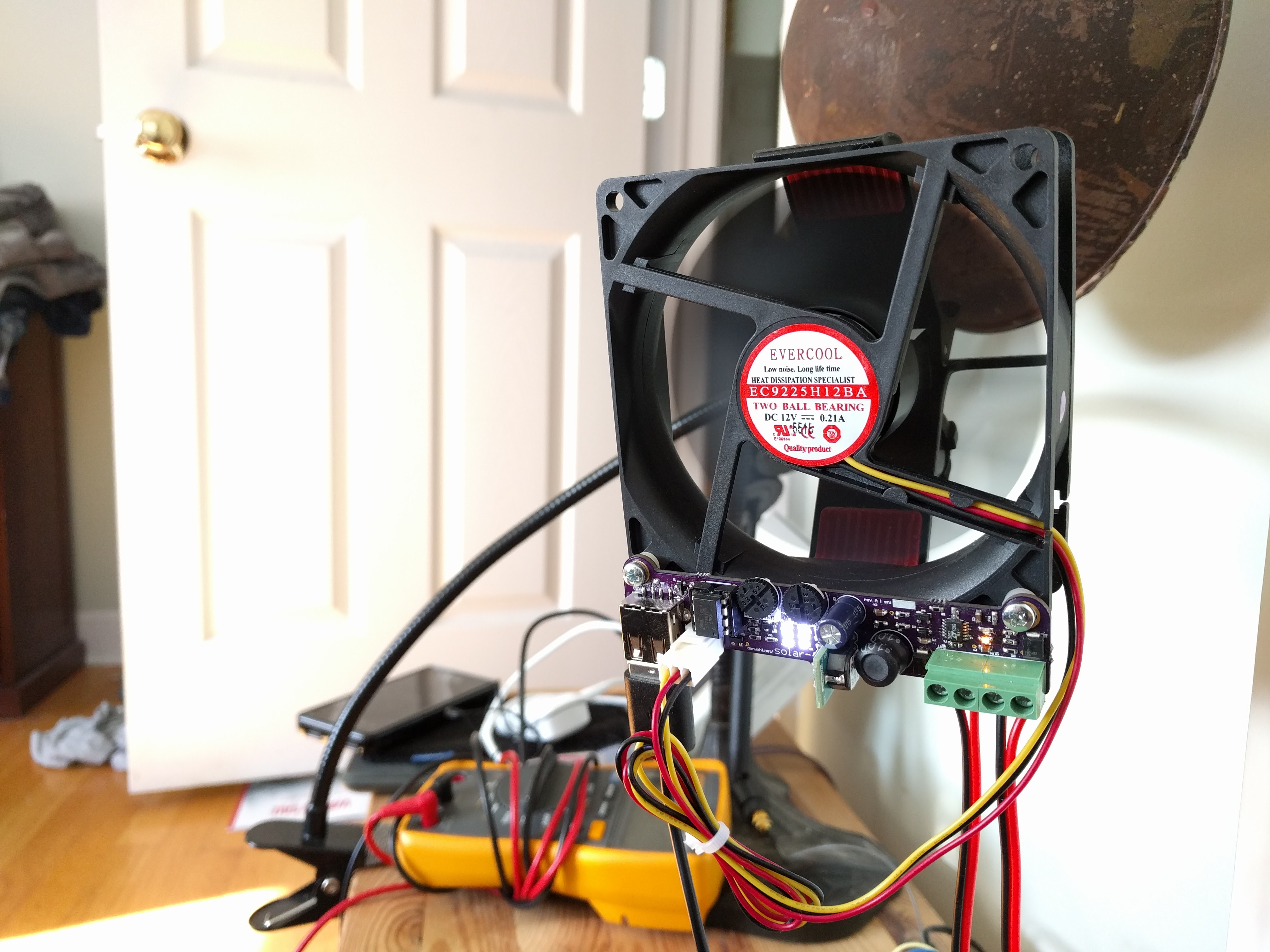

Here’s a closeup view of the first prototype (rev A) in action:

Money, it’s a hit

The per-unit cost for a one-off prototype build is currently $92.41, using the following components:

| Component | Link | Price |

|---|---|---|

| PCB | OSH Park ($14.05 for 3) | $4.68 |

| Electronics | Digikey (through Octopart) | $27.49 |

| Solar Panel | ECO-WORTHY 10W Solar Panel | $27.48 |

| Fan | StarTech 90 mm Fan | $7.78 |

| Battery | UB1250 Sealed Lead Acid Battery | $14.99 |

| Stand | BESTEK Cell Phone Clip Holder | $9.99 |

Combined with hours of manual soldering per board, this is obviously a non-starter (especially compared to a $2.50 bednet). However, this cost is likely to fall significantly with volume. In large quantities (10K or more), a conservative cost estimate for each component might look more like:

| Component | Notes | Price |

|---|---|---|

| PCB | (assembled) | $2.00 |

| Electronics | $10.00 | |

| Solar Panel | $20.00 | |

| Fan | $1.50 | |

| Battery | $8.00 | |

| Stand | $3.50 |

Which comes to about $45 overall - not great, but pretty close to the 2.5x to 10x bednet cost Briët projects in the response to his paper.

Future plans: wind light?

Is this cheap low enough for the solar fan to be a useful option? I have no idea, but the purpose of this writeup is partially to get feedback from the Malria community about what constitutes usefulness and cost effectiveness, and whether there are any relevant counterfactuals worth considering.

I also plan to post a follow-up outlining the prototyping and testing process, with more technical details about the design, and instructions for how to build one of your own.