So you want to mount a solar panel on your roof

So you want to mount a solar panel on your roof, but don’t have time for the city’s lengthy permitting process, and don’t want to shell out tens of thousands of dollars to a licensed solar contractor.

No problemo.

You’re an engineer, dammit, and it’s just a small solar panel. How hard can it be? You’ll get a bracket and a few cables, pitch it all up on the roof, drop the connectors down through an open window, and bam, you’re charging batteries. Right?

Well, come to think of it, you should probably make sure the panel doesn’t blow away. That would be pretty embarrassing. A few strategically placed sandbags should do the trick, but just how many are you going to need?

Engineering 101

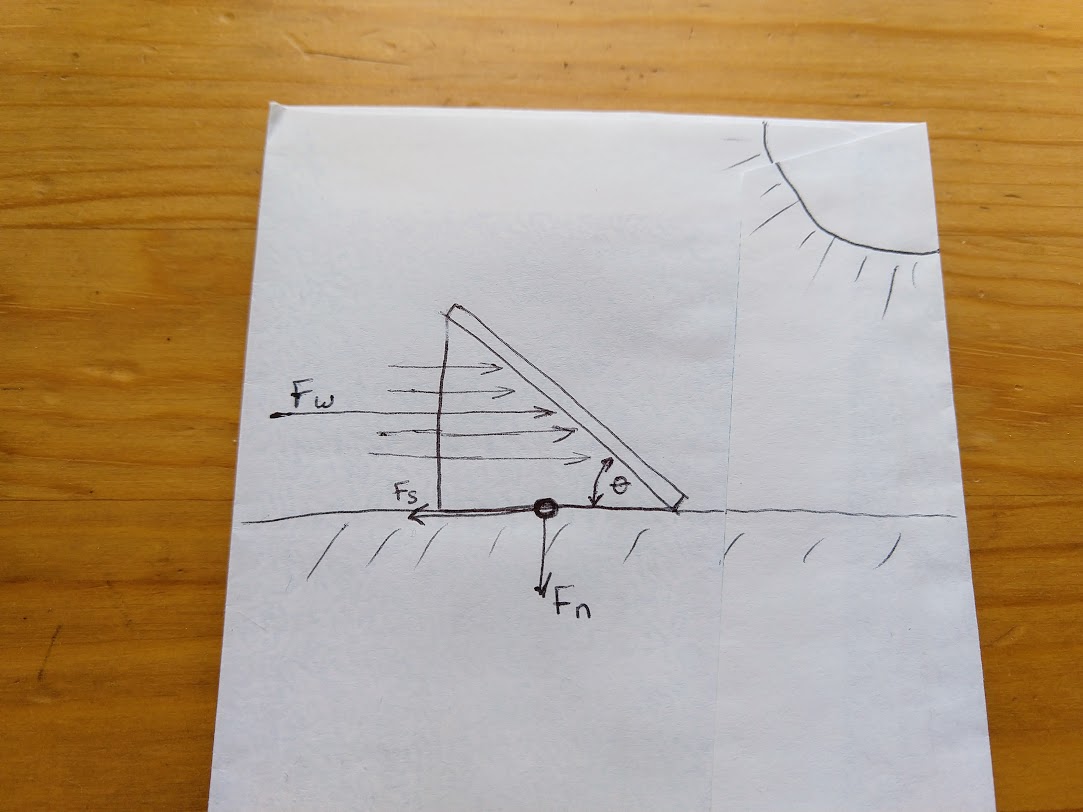

Like any well-trained (albeit extremely lapsed) mechanical engineer, you start by sketching a free body diagram on the back of the nearest envelope. You include a happy little sun in the corner for good measure.

You’re excited to realize that panel’s exposed profile (and therefore wind load) varies with the sine of mount angle \(\theta\), meaning that you only have to account for a fraction of the potential force that would be generated if mounted vertically.

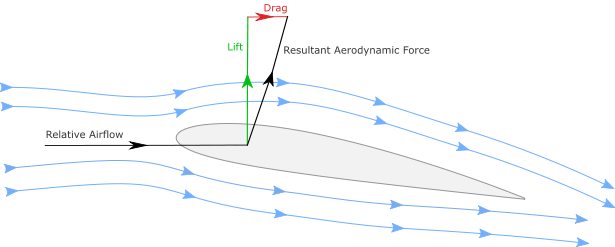

But looking at your artwork, something nags at you. The image of an inclined plane under horizontal wind load looks familiar in some way. It reminds you of another classic engineering diagram, though you can’t quite put your finger on…

Oh. Oh, crap.

It’s a wing.

It’s a wing

The problem, as you’ve just realized, is that an inclined plane under horizontal wind load generates lift, which makes your pretty little free body diagram totally obsolete, and vaults you headlong into the world of empirical aeronautics. See, when under intense wind load, your panel won’t just want to slide in the direction of the gust, it will also try to fly away like the world’s shittiest solar-powered aircraft. Your sandbags might help keep you grounded, but as lift increases, the normal force (\(F_n = m*g\)) and static friction (\(F_s = \mu_s*F_n\)) you’re relying on to keep your panel in place correspondingly decrease. And if the static force falls below the drag, things start to accelerate.

Damn. Well, maybe it won’t generate that much lift?

Lift

You start your research with the lift experts, NASA. Conveniently, they have a website dedicated to the aerodynamics of kites, a problem surprisingly analogous to the one you’re facing. The fact that this educational material is intended for children, not adults with relevant post-graduate degrees, causes you to feel absolutely no professional shame whatsoever. NASA sketches the following formulas for determining lift:

But on closer inspection, there’s a subtle problem. Kites are generally intended to be flown at a relatively small angle of attack, a property NASA assumes when providing a simple formula for lift coefficient:

For a thin flat plate at a low angle of attack , the lift coefficient Clo is equal to 2.0 times pi (3.14159) times the angle a expressed in radians (180 degrees equals pi radians): \(C_{lo} = 2 * pi * a\)

They don’t specify what qualifies as a “low” angle of attack, but based on your numbers it’s clearly less than your optimal mount angle. Since this equation won’t work, you do the next best thing and rent out time at the nearest wind tunnel to gather some empirical data on your specific panel. Because it’s not like anyone has done an equivalent experiment with rectangular planes of exactly the same aspect ratio and angle of attack and…

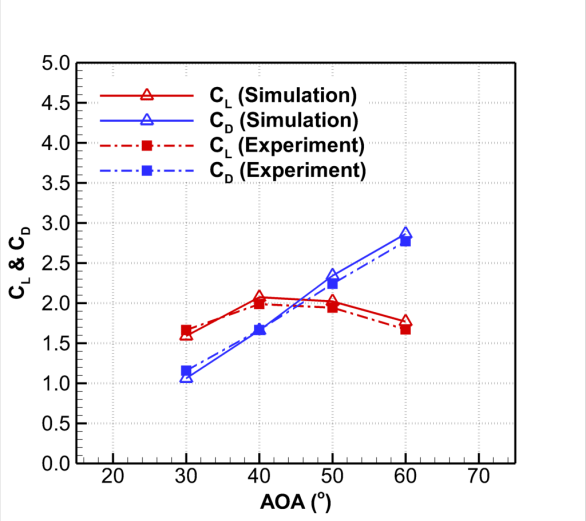

Someone has done the experiment

Thankfully, just before you put down a deposit on the wind tunnel, you find the exact paper you were looking for: Wake structure and aerodynamic performance of low aspect-ratio revolving plates at low reynolds number. Li et al. describe the effect of lift and drag on revolving rectangular planes, providing the ideal graph for your application:

From this image, you’re able to derive the lift and drag coefficients to plug into your spreadsheet. Now all that’s left is to figure out what wind speed you should plan for in the final calculation.

Windy city?

Because you’re working on another blog post about truisms (ETA soonish), you obviously know that:

- People call Chicago the windy city because of the wind.

- No, people call Chicago the windy city because their politicians are full of hot air.

- No really, the term windy city just refers to the wind coming off Lake Michigan. It’s cold!

- But doesn’t it something to do with New York City’s irritation over losing to the 1893 World’s Fair to a “frontier town”?

- Well here’s an quote from the 1876 Cincinnati Enquirer using the term in reference to their baseball rivalry with the White Sox etc.

Regardless, it does sometimes get meteorologically windy in Chicago, and knowing the maximum gust speed to expect is essential for sizing your sandbags. At a quick glance, Chicago’s record wind speed is a problematic 87 mph. But that measurement was way back in 1894, so how accurate can it be?

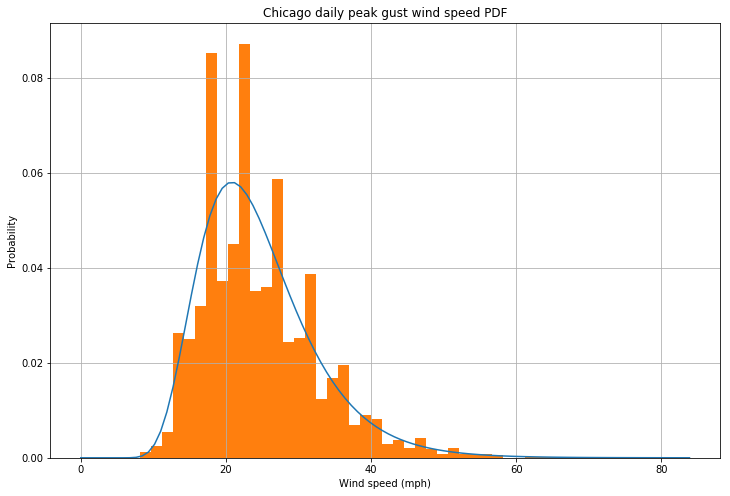

Ideally, you’d like to know the distribution of daily peak wind speeds, allowing you to select an appropriate upper threshold given a conservative confidence interval. So you do the reasonable thing and download 150 years worth of Chicago weather data for your analysis.

From this, you’re able to determine that the maximum daily wind gust at O’Hare is approximately log-normally distributed, with a 99.99% threshold value of approx. 75 mph. This is not much lower than the peak recorded gust, but since lift varies with the square of velocity, you’ll take what you can get. You crunch the numbers, and in order to safely secure your solar panel, it turns out you need only… 550 lbs worth of sandbags.

That is a lot of sand. But whatever; sandbags are cheap, it’s a one-time investment, and you’re in too deep to turn back now. Lugging them all up four flights of stairs and a ladder to the roof will be good exercise, at least!

Snow load

After a minute of satisfaction spent contemplating your engineering prowess, an unpleasant thought begins to gnaw. You live on the top floor, and your bedroom is directly beneath the proposed location of your sandbag-mounted solar panels. It would be really inconvenient if the roof collapsed. Exactly how much weight is your roof designed to support?

After a quick search, and follow-up message to a local architect friend, you determine that Chicago building code mandates that roofs withstand at least 25 lb/ft2 of snow pressure. Combining that with your proposed sandbag weight, you determine that you need only spread the load over a minimum of 22 ft2, or a hefty portion of your usable roof space. And even factoring in 1.5 °C of global warming, you do still expect some snow next winter…

Fuck.

Conclusion

Congratulations, you have now mounted a solar panel on your back deck, just as you intended all along.