Prostate Cancer Decision Matrix

A family member was recently diagnosed with an advancing form of prostate cancer, after years of monitoring the disease (via PSA) in a relatively benign form. Given his age (62) and Gleason score (7), he was advised to have undergo treatment soon, and given a portfolio of options including surgery and radiotherapy.

He asked me to help look into these options, which led me to create a model to help guide my understanding of the consequences of the disease and its treatments. Although I have no medical expertise whatsoever, I’m sharing the model, and my reasoning for it, with the hope that others might find it useful.

- Background

- Outcomes for the untreated

- Outcomes for the treated

- Just how bad are the side effects

- Full model and results

- What to do

Background

Before researching this topic, I didn’t know much about prostate cancer except that the surgery has the potential to cause erectile dysfunction, a reflection of the priorities of (relative) youth. A more detailed list of potential treatment side effects is shown below:

- Incontinence

- Impotence

- Infertility

- Hormonal changes

- Erectile Dysfunction

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

It was because of this scary list (and a vague impression from the medical skepticism community that radical therapies are sometimes over-prescribed) that my first instinct was to try to quantify the effects of prostate cancer without treatment.

Outcomes for the untreated

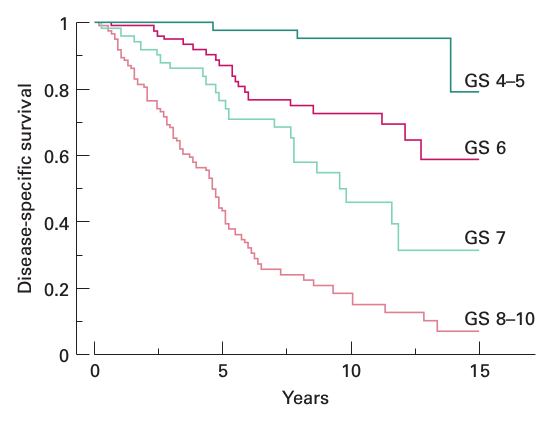

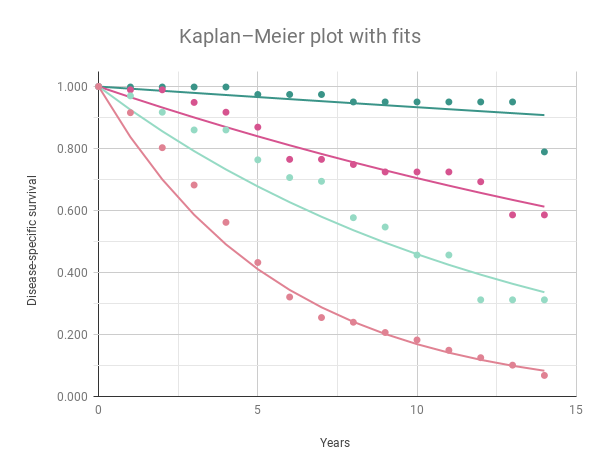

I primarily based my understanding on Prognostic value of the Gleason score in prostate cancer, a study which tracked the disease-specific survival of several hundred untreated men diagnosed from 1975-1990. The relevant Kaplan–Meier plot is shown below:

As a quick estimate, I modeled the disease-specific survival as an exponential function of time (\(survival = b*m^{years}\), with the constant \(b\) pegged to \(1.0\)). The resulting fits are as follows:

Gleason score m

4-5 0.993

6 0.966

7 0.925

8-10 0.837

To calculate the expected value of years remaining across the population of cancer patients with a specific Gleason score, I used the following formula (where \(U(0, 1)\) represents a uniform random variable):

\[years = {log(U(0, 1)) \over log(m)}\]Outcomes for the treated

The biggest surprise of my research was learning just how good the prognosis is, provided the disease is caught early enough in its progression. In fact, regardless of treatment option, prostate cancer seems to have a five year survival approaching 100%, up more than 30%(!) in the last 40 years.

Part of the gain in life expectancy can be attributed to technological improvements in the treatment process. Patients today have a portfolio of options that include the use of nuclear radiation, ultrasonics, robotic surgeons, and lasers: the future is right now.

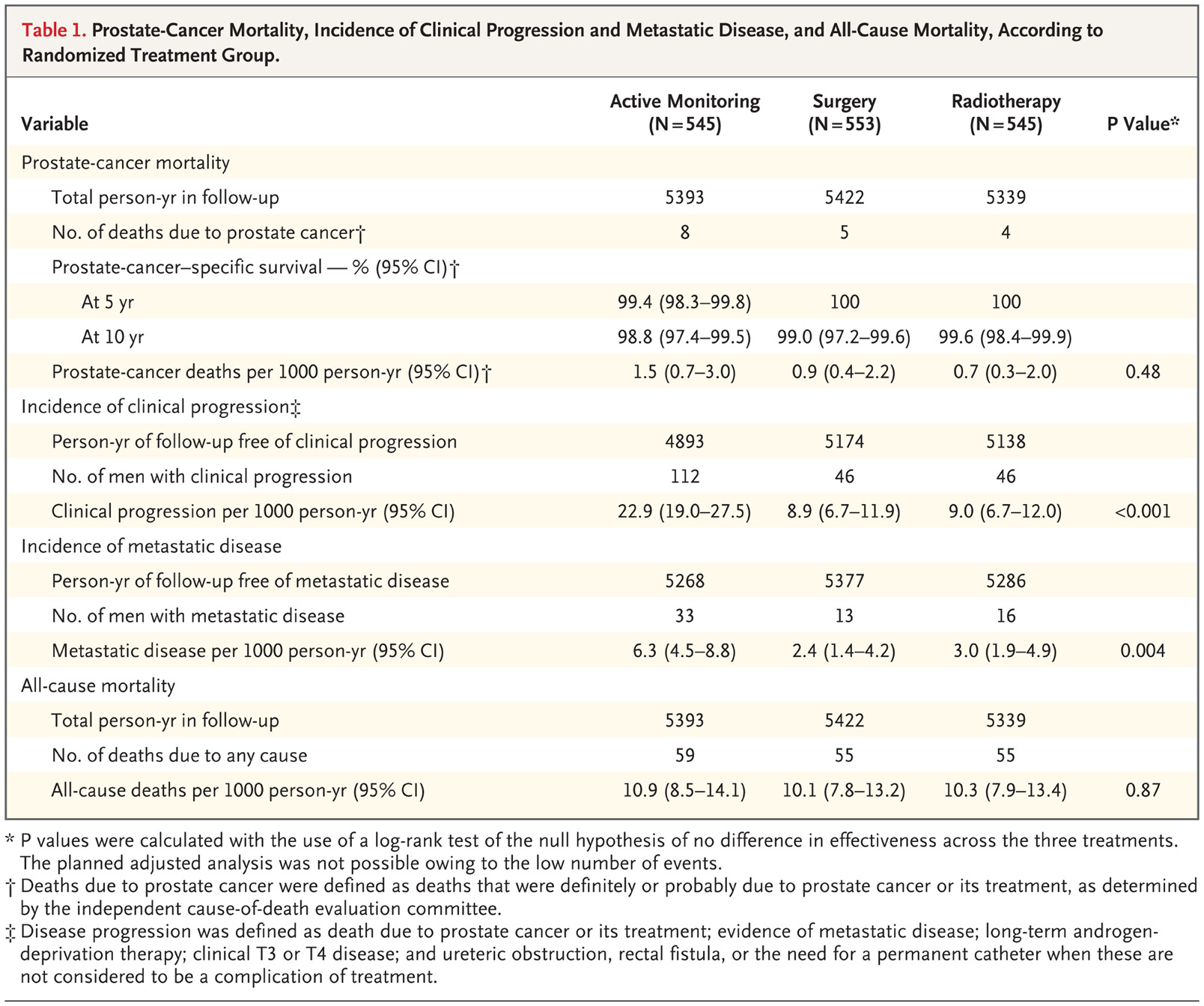

In order to model the effects of treatment, I used data from 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer, which includes the following table:

From the “Prostate-cancer deaths per 1000 person-yr” of the “Surgery” and “Radiotherapy” options, I derived a treatment mortality rate of approximately \(0.0008\) (or a survival rate \(m\) of \(0.9992\)). The expected value of disease-specific years remaining over the whole population can be calculated using the equation above.

Just how bad are the side effects

Finally, there’s the question of how to balance the negative side effects of treatment with expected gains in longevity. As with previous posts, I relied on the Disability Adjusted Life Years measure to quantify the expected harm of various treatment options. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation updated its Global Burden of Disease calculations in 2016, assigning the following disability weights to factors related to prostate cancer:

| Health state name | Disability weight | Sequela |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis and primary therapy phase of prostate cancer | 0.288 | Cancer, diagnosis and primary therapy |

| Impotence due to prostate cancer | 0.065 | Impotence and generic medication |

| Terminal phase of prostate cancer | 0.540 | Terminal phase, with medication (for cancers, end-stage kidney/liver disease) |

| Controlled phase of prostate cancer | 0.049 | Generic uncomplicated disease: worry and daily medication |

| Metastatic phase of prostate cancer | 0.451 | Cancer, metastatic |

| Incontinence due to prostate cancer | 0.181 | Incontinence and generic medication |

To generate a conservative estimate (with no discounting or age weighting) I assumed all treated patients suffered from permanent [impotence, incontinence, controlled phase side effects] (\(DW = 0.295\)), while untreated patients only experienced [controlled phase side effects] (\(DW = 0.049\)). This estimate considers non-treatment a kind of null hypothesis, meaning that any results favoring treatment are relatively significant.

Full model and results

To decide whether or not to opt for treatment, I ran a Monte Carlo simulation across the various outcomes using the following steps:

- Create a simulated cohort of 1000 individuals with identical age and Gleason score.

- Use an actuarial table to derive the life expectancy of each individual, assuming no prostate cancer.

- Estimate disease-specific life expectancy for each individual and treatment option, using the definitions from above.

- Calculate the DALYs for each individual and treatment option, summing the product of their disability weight with the result of step 3, and adding it to the difference between steps 2 and 3 (years lost through disability + death).

- Subtract the result of step 4 from step 2 for each individual and treatment option, resulting in the healthy years remaining given their prostate cancer diagnosis.

- From step 5 results, subtract the average “untreated” number from the “treated” number to find the difference in healthy years due to treatment.

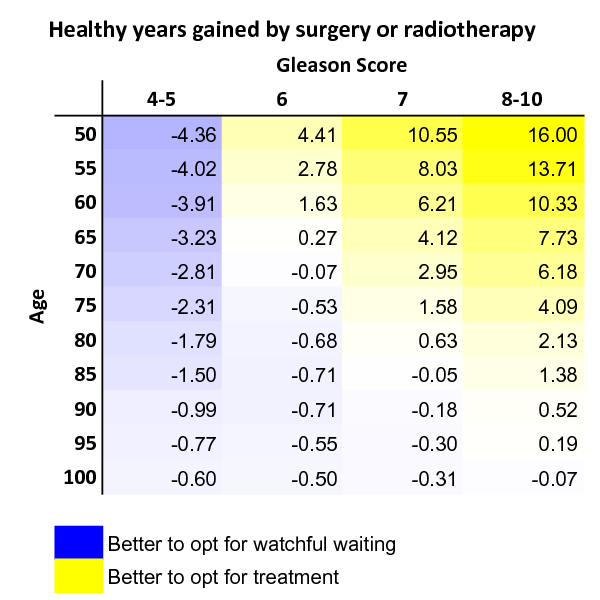

The results from step 6, calculated across age and Gleason score, are shown in the table below:

This should be interpreted as a conservative estimate of healthy years gained through treatment, with positive numbers indicating that surgery is likely a better option, given age and Gleason score.

The full model can be accessed here (you can make a copy to enter different parameters).

What to do

Based on my research, and the model derived above, I advised my family member that treatment seems like the best option, and is also a good option. Given the recent improvements in outcomes, an early diagnosis of prostate cancer is not a death sentence, and isn’t even likely to be the thing that kills you. And while the potential side effects might be unpleasant, the alternative is often worse.

As a final disclaimer, I am not a medical professional, so please disregard all of the above and talk with your doctor if you have any health concerns.